As tech’s social giants wrestle with antisocial demons that appear to be both an emergent property of their platform power, and a consequence of specific leadership and values failures (evident as they publicly fail to enforce even the standards they claim to have), there are still people dreaming of a better way. Of social networking beyond outrage-fuelled adtech giants like Facebook and Twitter.

There have been many such attempts to build a ‘better’ social network of course. Most have ended in the deadpool. A few are still around with varying degrees of success/usage (Snapchat, Ello and Mastodon are three that spring to mine). None has usurped Zuckerberg’s throne of course.

This is principally because Facebook acquired Instagram and WhatsApp. It has also bought and closed down smaller potential future rivals (tbh). So by hogging network power, and the resources that flow from that, Facebook the company continues to dominate the social space. But that doesn’t stop people imagining something better — a platform that could win friends and influence the mainstream by being better ethically and in terms of functionality.

And so meet the latest dreamer with a double-sided social mission: Openbook.

The idea (currently it’s just that; a small self-funded team; a manifesto; a prototype; a nearly spent Kickstarter campaign; and, well, a lot of hopeful ambition) is to build an open source platform that rethinks social networking to make it friendly and customizable, rather than sticky and creepy.

Their vision to protect privacy as a for-profit platform involves a business model that’s based on honest fees — and an on-platform digital currency — rather than ever watchful ads and trackers.

There’s nothing exactly new in any of their core ideas. But in the face of massive and flagrant data misuse by platform giants these are ideas that seem to sound increasingly like sense. So the element of timing is perhaps the most notable thing here — with Facebook facing greater scrutiny than ever before, and even taking some hits to user growth and to its perceived valuation as a result of ongoing failures of leadership and a management philosophy that’s been attacked by at least one of its outgoing senior execs as manipulative and ethically out of touch.

The Openbook vision of a better way belongs to Joel Hernández who has been dreaming for a couple of years, brainstorming ideas on the side of other projects, and gathering similarly minded people around him to collectively come up with an alternative social network manifesto — whose primary pledge is a commitment to be honest.

“And then the data scandals started happening and every time they would, they would give me hope. Hope that existing social networks were not a given and immutable thing, that they could be changed, improved, replaced,” he tells TechCrunch.

Rather ironically Hernández says it was overhearing the lunchtime conversation of a group of people sitting near him — complaining about a laundry list of social networking ills; “creepy ads, being spammed with messages and notifications all the time, constantly seeing the same kind of content in their newsfeed” — that gave him the final push to pick up the paper manifesto and have a go at actually building (or, well, trying to fund building… ) an alternative platform.

At the time of writing Openbook’s Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign has a handful of days to go and is only around a third of the way to reaching its (modest) target of $115k, with just over 1,000 backers chipping in. So the funding challenge is looking tough.

The team behind Openbook includes crypto(graphy) royalty, Phil Zimmermann — aka the father of PGP — who is on board as an advisor initially but billed as its “chief cryptographer”, as that’s what he’d be building for the platform if/when the time came.

Hernández worked with Zimmermann at the Dutch telecom KPN building security and privacy tools for internal usage — so called him up and invited him for a coffee to get his thoughts on the idea.

“As soon as I opened the website with the name Openbook, his face lit up like I had never seen before,” says Hernández. “You see, he wanted to use Facebook. He lives far away from his family and facebook was the way to stay in the loop with his family. But using it would also mean giving away his privacy and therefore accepting defeat on his life-long fight for it, so he never did. He was thrilled at the possibility of an actual alternative.”

On the Kickstarter page there’s a video of Zimmermann explaining the ills of the current landscape of for-profit social platforms, as he views it. “If you go back a century, Coca Cola had cocaine in it and we were giving it to children,” he says here. “It’s crazy what we were doing a century ago. I think there will come a time, some years in the future, when we’re going to look back on social networks today, and what we were doing to ourselves, the harm we were doing to ourselves with social networks.”

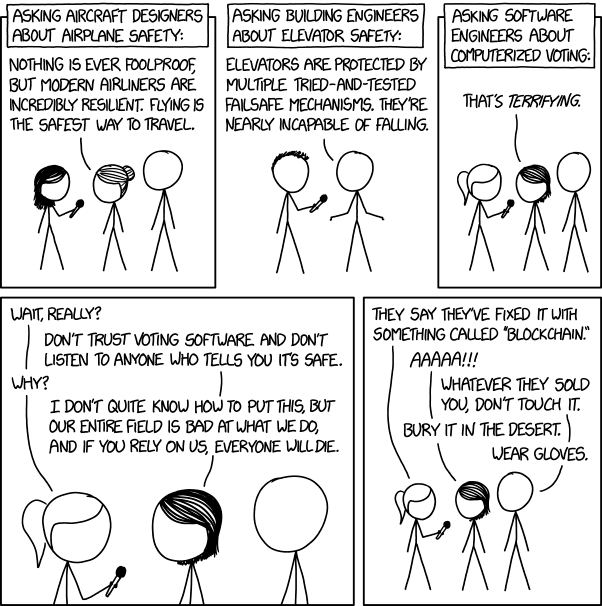

“We need an alternative to the social network work revenue model that we have today,” he adds. “The problem with having these deep machine learning neural nets that are monitoring our behaviour and pulling us into deeper and deeper engagement is they already seem to know that nothing drives engagement as much as outrage.

“And this outrage deepens the political divides in our culture, it creates attack vectors against democratic institutions, it undermines our elections, it makes people angry at each other and provides opportunities to divide us. And that’s in addition to the destruction of our privacy by revenue models that are all about exploiting our personal information. So we need some alternative to this.”

Hernández actually pinged TechCrunch’s tips line back in April — soon after the Cambridge Analytica Facebook scandal went global — saying “we’re building the first ever privacy and security first, open-source, social network”.

We’ve heard plenty of similar pitches before, of course. Yet Facebook has continued to harvest global eyeballs by the billions. And even now, after a string of massive data and ethics scandals, it’s all but impossible to imagine users leaving the site en masse. Such is the powerful lock-in of The Social Network effect.

Regulation could present a greater threat to Facebook, though others argue more rules will simply cement its current dominance.

Openbook’s challenger idea is to apply product innovation to try to unstick Zuckerberg. Aka “building functionality that could stand for itself”, as Hernández puts it.

“We openly recognise that privacy will never be enough to get any significant user share from existing social networks,” he says. “That’s why we want to create a more customisable, fun and overall social experience. We won’t follow the footsteps of existing social networks.”

Data portability is an important ingredient to even being able to dream this dream — getting people to switch from a dominant network is hard enough without having to ask them to leave all their stuff behind as well as their friends. Which means that “making the transition process as smooth as possible” is another project focus.

Hernández says they’re building data importers that can parse the archive users are able to request from their existing social networks — to “tell you what’s in there and allow you to select what you want to import into Openbook”.

These sorts of efforts are aided by updated regulations in Europe — which bolster portability requirements on controllers of personal data. “I wouldn’t say it made the project possible but… it provided us a with a unique opportunity no other initiative had before,” says Hernández of the EU’s GDPR.

“Whether it will play a significant role in the mass adoption of the network, we can’t tell for sure but it’s simply an opportunity too good to ignore.”

On the product front, he says they have lots of ideas — reeling off a list that includes the likes of “a topic-roulette for chats, embracing Internet challenges as another kind of content, widgets, profile avatars, AR chatrooms…” for starters.

“Some of these might sound silly but the idea is to break the status quo when it comes to the definition of what a social network can do,” he adds.

Asked why he believes other efforts to build ‘ethical’ alternatives to Facebook have failed he argues it’s usually because they’ve focused on technology rather than product.

“This is still the most predominant [reason for failure],” he suggests. “A project comes up offering a radical new way to do social networking behind the scenes. They focus all their efforts in building the brand new tech needed to do the very basic things a social network can already do. Next thing you know, years have passed. They’re still thousands of miles away from anything similar to the functionality of existing social networks and their core supporters have moved into yet another initiative making the same promises. And the cycle goes on.”

He also reckons disruptive efforts have fizzled out because they were too tightly focused on being just a solution to an existing platform problem and nothing more.

So, in other words, people were trying to build an ‘anti-Facebook’, rather than a distinctly interesting service in its own right. (The latter innovation, you could argue, is how Snap managed to carve out a space for itself in spite of Facebook sitting alongside it — even as Facebook has since sought to crush Snap’s creative market opportunity by cloning its products.)

“This one applies not only to social network initiatives but privacy-friendly products too,” argues Hernández. “The problem with that approach is that the problems they solve or claim to solve are most of the time not mainstream. Such as the lack of privacy.

“While these products might do okay with the people that understand the problems, at the end of the day that’s a very tiny percentage of the market. The solution these products often present to this issue is educating the population about the problems. This process takes too long. And in topics like privacy and security, it’s not easy to educate people. They are topics that require a knowledge level beyond the one required to use the technology and are hard to explain with examples without entering into the conspiracy theorist spectrum.”

So the Openbook team’s philosophy is to shake things up by getting people excited for alternative social networking features and opportunities, with merely the added benefit of not being hostile to privacy nor algorithmically chain-linked to stoking fires of human outrage.

The reliance on digital currency for the business model does present another challenge, though, as getting people to buy into this could be tricky. After all payments equal friction.

To begin with, Hernández says the digital currency component of the platform would be used to let users list secondhand items for sale. Down the line, the vision extends to being able to support a community of creators getting a sustainable income — thanks to the same baked in coin mechanism enabling other users to pay to access content or just appreciate it (via a tip).

So, the idea is, that creators on Openbook would be able to benefit from the social network effect via direct financial payments derived from the platform (instead of merely ad-based payments, such as are available to YouTube creators) — albeit, that’s assuming reaching the necessary critical usage mass. Which of course is the really, really tough bit.

“Lower cuts than any existing solution, great content creation tools, great administration and overview panels, fine-grained control over the view-ability of their content and more possibilities for making a stable and predictable income such as creating extra rewards for people that accept to donate for a fixed period of time such as five months instead of a month to month basis,” says Hernández, listing some of the ideas they have to stand out from existing creator platforms.

“Once we have such a platform and people start using tips for this purpose (which is not such a strange use of a digital token), we will start expanding on its capabilities,” he adds. (He’s also written the requisite Medium article discussing some other potential use cases for the digital currency portion of the plan.)

At this nascent prototype and still-not-actually-funded stage they haven’t made any firm technical decisions on this front either. And also don’t want to end up accidentally getting into bed with an unethical tech.

“Digital currency wise, we’re really concerned about the environmental impact and scalability of the blockchain,” he says — which could risk Openbook contradicting stated green aims in its manifesto and looking hypocritical, given its plan is to plough 30% of its revenues into ‘give-back’ projects, such as environmental and sustainability efforts and also education.

“We want a decentralised currency but we don’t want to rush into decisions without some in-depth research. Currently, we’re going through IOTA’s whitepapers,” he adds.

They do also believe in decentralizing the platform — or at least parts of it — though that would not be their first focus on account of the strategic decision to prioritize product. So they’re not going to win fans from the (other) crypto community. Though that’s hardly a big deal given their target user-base is far more mainstream.

“Initially it will be built on a centralised manner. This will allow us to focus in innovating in regards to the user experience and functionality product rather than coming up with a brand new behind the scenes technology,” he says. “In the future, we’re looking into decentralisation from very specific angles and for different things. Application wise, resiliency and data ownership.”

“A project we’re keeping an eye on and that shares some of our vision on this is Tim Berners Lee’s MIT Solid project. It’s all about decoupling applications from the data they use,” he adds.

So that’s the dream. And the dream sounds good and right. The problem is finding enough funding and wider support — call it ‘belief equity’ — in a market so denuded of competitive possibility as a result of monopolistic platform power that few can even dream an alternative digital reality is possible.

In early April, Hernández posted a link to a basic website with details of Openbook to a few online privacy and tech communities asking for feedback. The response was predictably discouraging. “Some 90% of the replies were a mix between critiques and plain discouraging responses such as “keep dreaming”, “it will never happen”, “don’t you have anything better to do”,” he says.

(Asked this April by US lawmakers whether he thinks he has a monopoly, Zuckerberg paused and then quipped: “It certainly doesn’t feel like that to me!”)

Still, Hernández stuck with it, working on a prototype and launching the Kickstarter. He’s got that far — and wants to build so much more — but getting enough people to believe that a better, fairer social network is even possible might be the biggest challenge of all.

For now, though, Hernández doesn’t want to stop dreaming.

“We are committed to make Openbook happen,” he says. “Our back-up plan involves grants and impact investment capital. Nothing will be as good as getting our first version through Kickstarter though. Kickstarter funding translates to absolute freedom for innovation, no strings attached.”

You can check out the Openbook crowdfunding pitch here.