Vinton Gray Cerf, a co-founder of

i4j -- innovation for jobs, is widely hailed as one of "the fathers of the Internet". Cerf was a manager for the United States' Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) funding groups to develop TCP/IP technology and currently serves as the Chief Evangelist of the Internet for Google.

David Nordfors

Contributor

More posts by this contributor

There is a disconnection between the pace and progress of the technical achievements made by innovators and entrepreneurs and the ways in which those technologies have added to human happiness.

We have increased our technological powers many times and still we are not happier; we do not have more time for the things we find meaningful.

We could use our powers for making each other — and thereby ourselves — more valuable, but instead we are fearing to lose our jobs to machines and be considered worthless by the economy. The link between better technology and better lives overall has become so confusing that many people no longer reflect upon its existence.

We are co-founders of i4j — Innovation for Jobs, an eclectic community of thought leaders that has been exchanging ideas since 2012 about how innovation can disrupt unemployment and create better jobs. We believe we have found an approach for doing so that we lay forth in our new book, “The people centered economy – the new ecosystem for work.” The book presents a system of ideas, ranging from helicopter perspective down to details of scenarios. It puts theory in perspective with a number of relevant real-life case examples written by i4j members, founders of major companies, such as LinkedIn, startup CEOs, investors, foundation directors and social entrepreneurs.

The problem today, we suggest, is that our innovation economy is not primarily about making people more valuable; it is instead about reducing costs.

The main danger is easy to summarize: when workers are seen as a cost (which is now the case), cost-saving, efficient technologies will compete to lower their cost and thereby their value. The “better” the innovation, the lower their value. People are struggling to stay valuable in a changing world, and innovation is not helping them, except for the chosen few. The need to be valued and to be in demand are part of our human nature. Innovation can, and should, make people more valuable.

The economy is about people who need, want, and value each other. When we need each other more, the economy can grow. When we need each other less, it shrinks. We need innovation that makes people need each other more.

The purpose of innovation should be a sustainable economy, where we work with people we like, are valued by people we do not know and provide for the people we love

If innovation does this, we will prosper.

The present “task-centered “economy that sees people as cost is plagued by many symptoms of its lethal illness. We present several in the book, here is one of them.

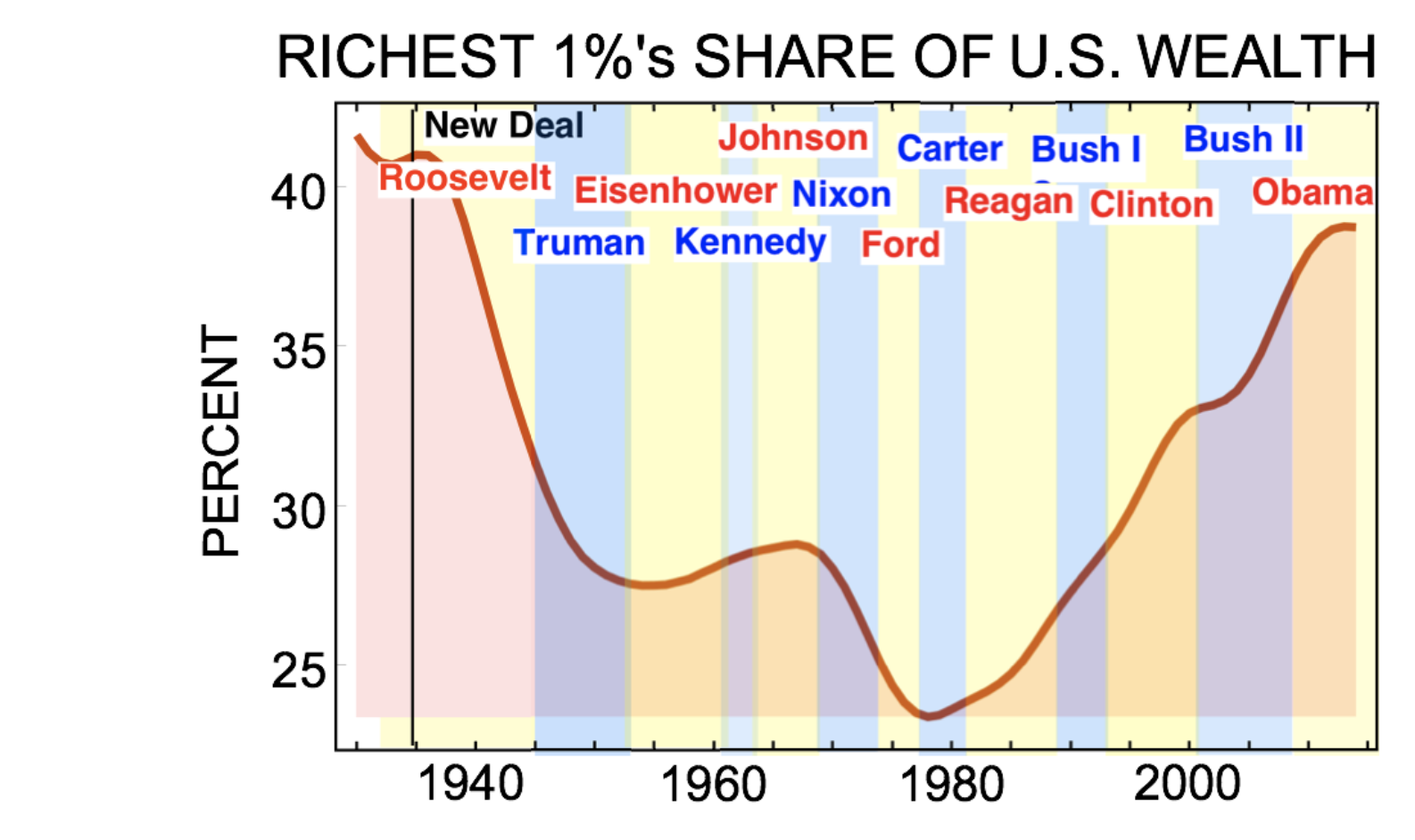

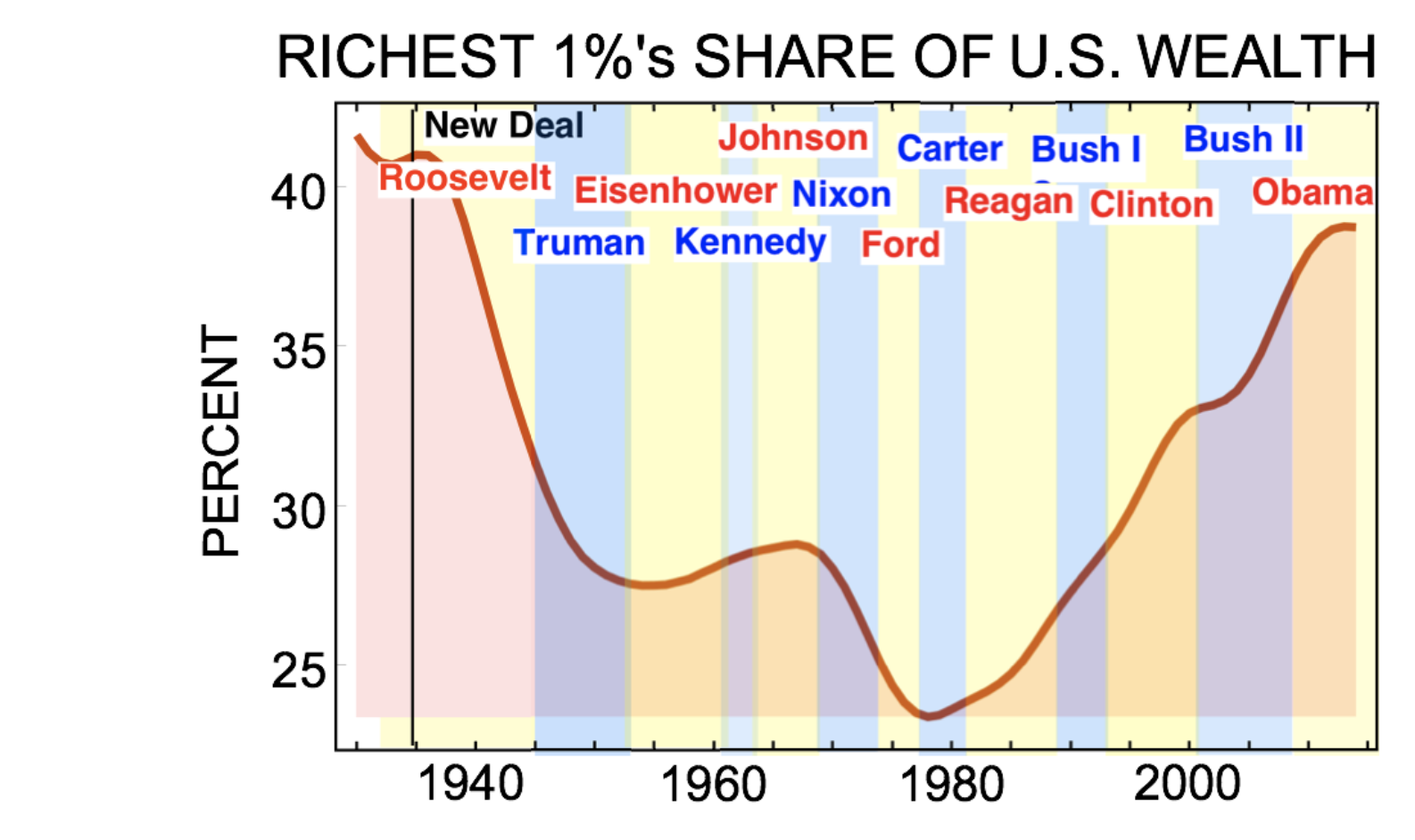

The rise of the working middle class boosted by Roosevelt’s “New Deal” has been all but wiped out. People like blaming their political opponents for these kinds of things but the wealth gap has been growing steadily, since 1980, under Republicans and Democrats alike. No, this is beyond politics.

The root cause for all this is the very essence of our task-centered economy: placing tasks, products and other things at the center of the value proposition instead of people. It seems very natural to see it this way, because, after all, you want your house painted and there are painters who want to paint it – how can it work any other way? Yet, wanting things done better and cheaper, combined with innovation that makes that happen, is the cause of the troubles.

Companies will cut labor costs, as automation and offshoring lets them. When people earn less they will have less money to spend. The companies adapt to their shrinking purses by innovating still cheaper products and services and cutting labor costs even more. It is a spiral pointing downward toward a point zero where people earn and spend zero.

At the heart of this problem is the old saying, “A dollar saved is a dollar earned.” This maxim rings true to you and me in daily life, and it applies to companies. But paradoxically, in the economy, the opposite is true: a dollar saved is actually a dollar lost.

One person’s earning is always other people’s spending and if everyone spends less, people earn – on average – less. Economies run on the spending and re-spending of the same money. Velocity counts. Economic growth is killed by companies that are competing solely for profits. We are not saying it’s wrong to save and not be wasteful, it’s good and necessary, but that is not earning. Saying that saving and earning are the same introduces the paradox and is a recipe for a failed economy.

It might not be possible to solve the growth-profit paradox in a task-centered economy, because it is inherent in the mindset. This mindset always looks at work and asks what is the most cost-efficient way of doing it. What keeps the economy from collapsing is the inherent limits of automating work. Workers have remained a necessary, if undesired, cost. But what will be the outcome if artificial intelligence allows almost all work to be automated? Now the task-centered mindset creates an implosion. With a task-centered mindset, innovation is set to kill economies.

Is the AI and machine learning revolution that seem to threaten our jobs different from previous industrial revolutions? The times are different but you may be shocked by the similarity in the patterns of change. Read the following excerpt of original text from the Communist Manifesto, where Bourgeoisie is replaced with Internet Entrepreneurs, Proletariat with On-Demand Workers, Civilization with Digital Economy, and Revolution with Disruption.

“Internet entrepreneurship cannot exist without constant disruption of markets, bringing uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions. Internet entrepreneurship has created the modern working class — the on-demand workers, who must sell themselves in bits and pieces. They have become a commodity, exposed to the whims of the market. Their work has lost all individual character, and all charm. It is only the most simple and most easily acquired work that is required of them. The on-demand worker’s production cost is limited almost entirely to his living costs. But the price of a commodity is in the long run equal to its production cost. Therefore, the more the individual character disappears from his work, the wage decreases in proportion. The lower middle class will gradually become on-demand workers, partly because their specialized skills are rendered worthless by new methods of production.”

The accuracy of this message from the grave is nothing less than spooky. The analogy is clear, as is the message it sends: Internet entrepreneurship is the new bourgeoisie.

Universal Basic Income (UBI) can provide basic security, but it can’t replace work. People will always need to be able to depend on strangers — even adversaries. The day people no longer need to work, why should they want to depend on people they don’t know or don’t like? Utopian ideas about UBI don’t provide an answer. Meaningful paid work does and is the glue that holds societies together. The utopian UBI discussion is just another symptom of lost bearings. We start debating which jobs can’t be done by machines, whether machines can become exactly like people, whether machines should pay taxes, and so on. These are all interesting philosophical questions, but discussing them will hardly solve the practical problem: innovation is disrupting society. We need practical solutions. The first requirement is to be able to see them.

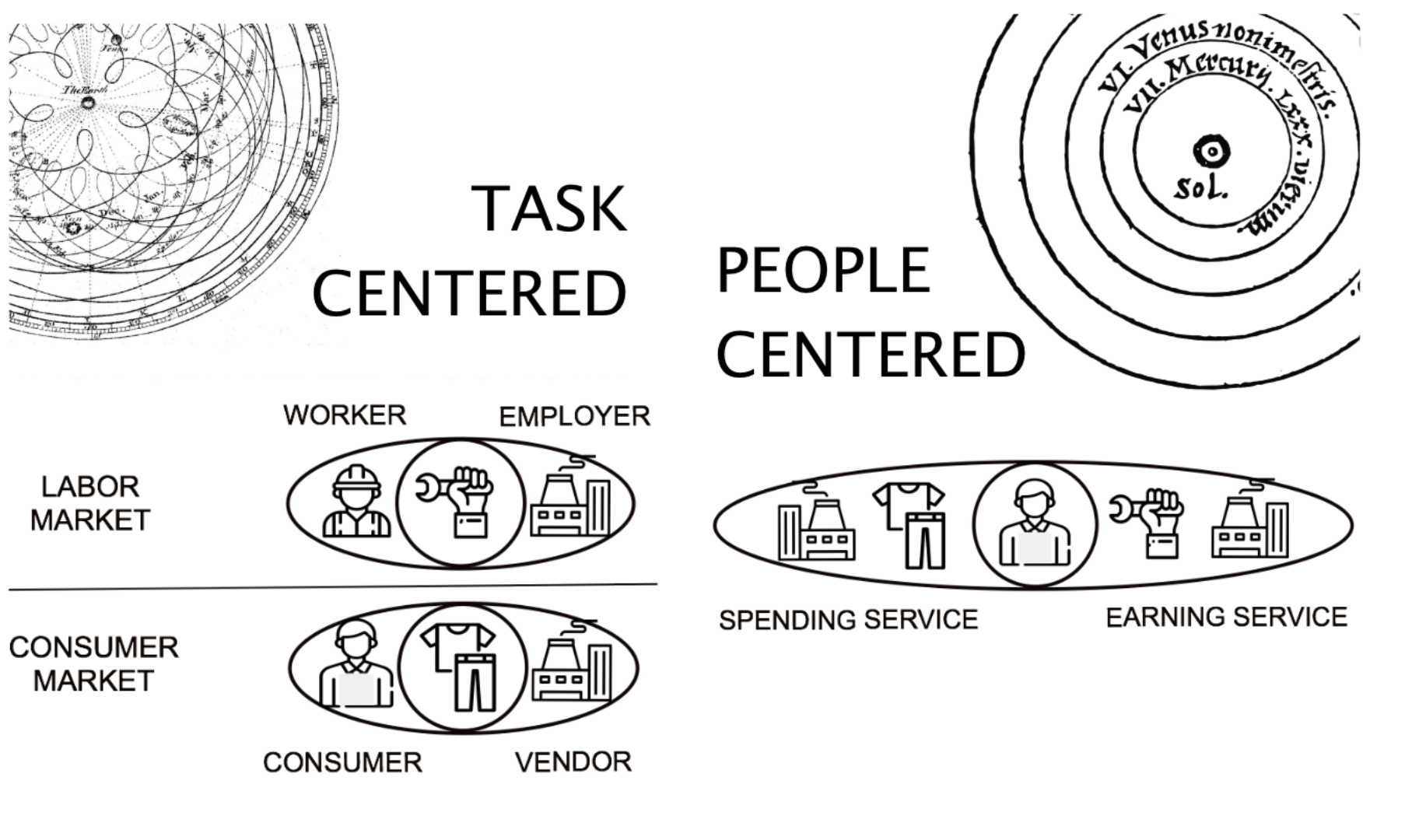

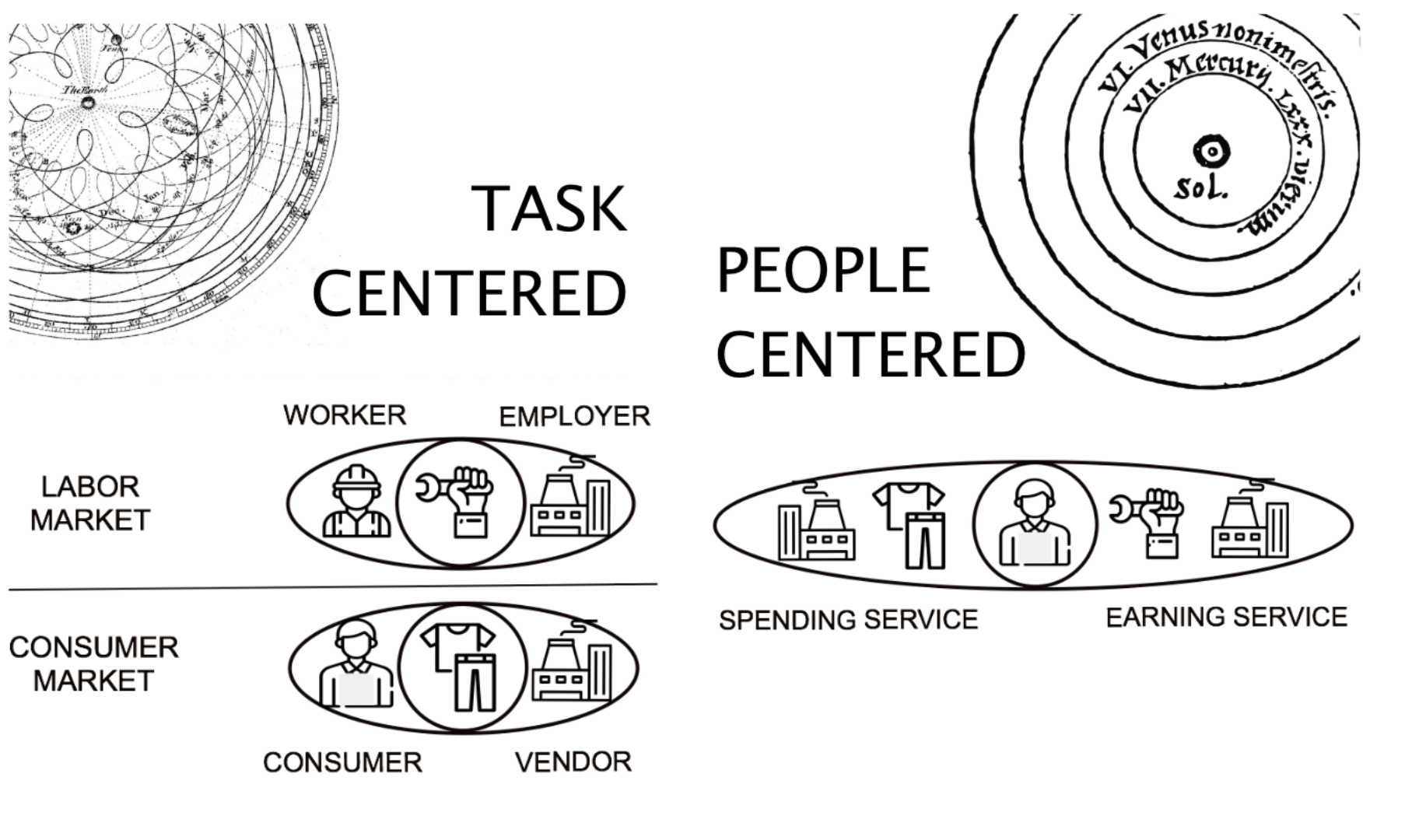

A key reason behind the confusion is that lack of perspective; reality needs a new lens. We can’t explain what we see because the good old ideas that once made things understandable are now making the world unintelligible instead. This happens often in history — for example, people in the middle ages had long thought that the earth was the center of the universe, but as scientists traced their movements in the sky, the more complex and incomprehensible their orbits became. But simply by switching perspective, placing the sun at the center, complicated orbits were transformed into nearly-circular ellipses of great simplicity. This was the “Copernican Revolution”.

We suggest that doing a similar switch: that moving people to the center can be equally constructive. A “people-centered economy” view could enable us to simplify the innovation economy and engineer it better just as the “Copernican revolution” did for physics and astronomy. The economy is all about people, after all, so it seems only natural to place us at the center. And it does indeed make the economy look simpler, as shown in the figure.

Our present task-centered view splits people in two: a worker-persona who earns money on a labor market, and a consumer persona who spends the money on a consumer market: a disconnected reality in which we are living double lives! It might seem like the time- tested and obvious view, but it is actually complex, disconnected, and wrong.

Switch to the people-centered lens and we are whole again. The labor and consumer markets are replaced by a single market where people are offered two kinds of services, one for earning money and another for spending it. It is a less confusing picture. By definition, organizations serve us, not the other way around. They are the ecosystem in which we are embedded, which helps us create and exchange value between each other.

Just by switching to a people-centered lens, things fall more neatly into place around us:

A people centered economy has a simple and handy definition of the economy: People create and exchange value, served by organizations.

Seen through the people-centered lens, the thorny question of the future of work is rephrased: “Is AI-innovation being applied more to earning or to spending?” The simple answer is “spending” and the straightforward conclusion is that we need more innovation that helps people earn. Through the people-centered lens an obvious “rule number one” of a sustainable innovation economy becomes clear to see:

We need as much innovation that helps us earn as there is innovation that helps us spend.

Today, we are surrounded by excellent innovation for spending, but there is very little good innovation for earning and none for earning a livelihood.

We need startups that compete to innovate a really good earning-service, perhaps something like this:

“Dear Customer, we offer to help you earn a better living in more meaningful ways.

We will use AI to tailor a job to your unique skills, talents, and passions.

We will match you in teams with people you like working with.

You can choose between kinds of meaningful work.

You will earn more than you do today.

We will charge a commission.

Do you want our service?”

The good news is that the world’s labor market is ready to be disrupted by innovative new ways to satisfy the customers’ needs and wants to earn a good livelihood.

And the market opportunity for this is huge! Here is an estimate: According to Gallup’s chairman Jim Clifton, of some five billion people in the world who are of working age, three billion want to work and earn income. Most of them want a full-time job with steady pay, but only 1.3 billion have one. Out of these 1.3 billion people with jobs, only 200 million are “engaged” in what they do for a living — i.e., they enjoy what they do and look forward to each working day. These lucky few, however, are outnumbered 2:1 by those who are disengaged, expressing displeasure and even undermining the work of others. The remainder of the population are simply disengaged from what they are doing, dragging their feet through the work day.

This is the sad state of the global workforce that creates roughly a hundred trillion dollars’ worth of products and services every year. Humanity is running at a fraction of its capacity. Imagine using modern information technology to tailor jobs to every one of the three billion people wanting to work — work that is well matched with their unique skills, talents, and passions; work in which they are assigned to valuable tasks and partnered with people they like to work with. In such a world, the average world citizen would be able to generate several times the per-person value created today. How much more value would they create than the unhappy, mismatched workforce of today?

A doubling of value creation is surely low, but even that figure adds $100 trillion in value to the world economy. If the job providers charged the same commission as Uber does, 25 percent, on the incomes people earned through their services, this would generate revenues of $50 trillion from commissions alone, plus additional revenues from add-on services, such as liability insurance and health benefits.

At this size, tailoring better ways for people to earn their livelihood would be the single largest market in the world. Even at only one percent commission, hardly noticeable for the earners, the potential market size is two trillion dollars. We think this should be an attractive opportunity for entrepreneurs, investors and governments to explore.

“Tailoring jobs” is a virgin market waiting to happen, because previously we did not have the technology for it. But now, since only a year or two, we have good enough tools. Increasing smartphone penetration and new capacities like cloud computing and big data analytics could, in principle, tailor rewarding jobs for every person on earth. Even if this is unrealistic today, it is still a huge potential market, even if it is applied to only a fraction of the world population looking for a good job. It will be wrong to assume that the workers must belong the well-educated elite, because they are already well served with good job offers. Quite the opposite, The big market for AI-tailored jobs is the vast majority of excluded, un- and underemployed people who are lacking the opportunity to live up to their abilities.

A simple innovation that helps many millions of these people can be a much better business than something advanced that helps the already well-served. It is similar to how, before the first industrial revolution, the most successful manufacturers sold expensive things to rich people.

With the introduction of mass production this changed in an, at the time, surprising and unforeseeable way, when selling cheap things to the masses became the new highway to success. Back then, the people running the old economies could hardly imagine how selling crafted goods to people with thin wallets could be better business than selling them to kings.

Today, as we are introducing mass-personalized goods and services, many business leaders will have great difficulties imagining how creating special jobs for people with little income can be better business than tailoring jobs for the engineers that companies compete for.

We are at the beginning of a revolution in strength finding, education, matchmaking, HR, and new opportunities in a long-tail labor market.

The i4j community includes entrepreneurs and investors who are interested in exploring this opportunity and we are welcoming more to join. An ecosystem of critical mass can open the doors to a people-centered economy and we intend to help it happen.