Snapchat is secretly planning the launch of its first full-fledged developer platform, currently called Snapkit. The platform’s prototypes indicate it will let other apps offer a ‘login with Snapchat’ options, use the Bitmoji avatars it acquired, and host a version of Snap’s full-featured camera software that can share back to Snapchat. Multiple sources confirm Snap Inc is currently in talks with several app developers to integrate Snapkit.

The platform could breathe new life into plateauing Snapchat by colonizing the mobile app ecosystem with its login buttons and content. Facebook used a similar strategy to become a ubiquitous utility with tentacles touching everyone’s business. But teens, long skeptical of Facebook and unsettled by the recent Cambridge Analytica scandal, could look to Snapchat for a privacy-safe way to log in to other apps without creating a new username and password.

We’ve spoken with Snapchat and are awaiting a response to our request for comment on the news.

Snapchat is making a big course correction in its strategy here after years of rejecting outside developers. In 2014, unofficial apps that let you surreptiously save Snaps but required your Snapchat credentials caused data breaches, leading the company to reiterate its ban on using them. It also shut off sharing from a popular third-party music video sharing app called Mindie. In fact, Snap’s terms of service still say “You will not use or develop any third-party applications that interact with the Services or other users’ content or information without our written consent.”

A year ago I wrote that “Snap’s anti-developer attitude is an augmented liability” since it would be tough to populate the physical world with AR experiences unless it has help like Facebook had started recruiting. By December, Snapchat had launched Lens Studio which lets brands and developers build limited AR content for the app. And it’s been building out its cadre of marketing and analytics partners that brands can work with.

Yet until now, Snapchat hadn’t created functionality that developers could use in their own apps. Snapkit will change that. We don’t know when it will be announced or launched, or who will be the initial developers who take advantage of it. But with Snapchat slipping to its lowest user growth rate ever after being pummeled by competition from Facebook and Instagram, the company needs more than a puppy face filter to regain the spotlight.

SnapPlat

According to sources familiar with Snap’s discussions with potential developers, Snapkit’s login with Snapchat feature is designed to let users sign up for new apps with their Snapchat credentials instead of creating new ones. Since Snap doesn’t collect much personal info about you unlike Facebook, there’s less data to worry about accidentally giving to developers or them misusing. Displaying its branded button on various app’ signup pages could lure in new Snapchat users or reengage lapsed ones. It’s also the key to developing tighter ties between Snap and other apps.

According to sources familiar with Snap’s discussions with potential developers, Snapkit’s login with Snapchat feature is designed to let users sign up for new apps with their Snapchat credentials instead of creating new ones. Since Snap doesn’t collect much personal info about you unlike Facebook, there’s less data to worry about accidentally giving to developers or them misusing. Displaying its branded button on various app’ signup pages could lure in new Snapchat users or reengage lapsed ones. It’s also the key to developing tighter ties between Snap and other apps.

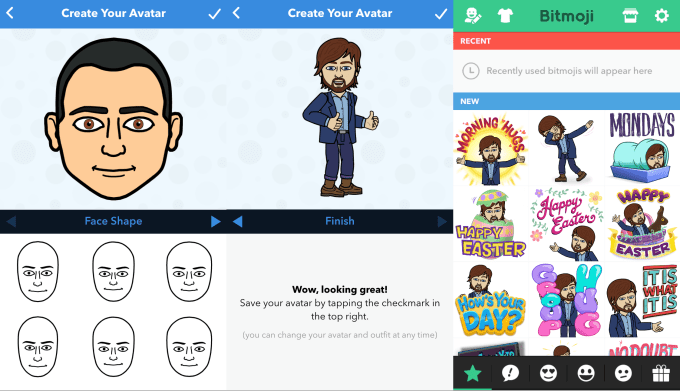

One benefit of another app knowing who you are on Snapchat which the company plans to provide with Snapkit is the ability to bring your Bitmoji avatar with you. Snapchat acquired Bitmoji’s parent company Bitstrips for just $64.2 million in 2016, but the cartoonish personalized avatar app has been a staple of the top 10 chart since. It remains one of Snapchat’s most differentiated offerings, as Facebook has only recently begun work on its clone called Facebook Avatars.

While Bitmoji has offered a keyboard full of your avatar in different scenes, Snapkit could make it easy to add yours as stickers on photos or in other ways in third-party apps. Seeing them across the mobile universe could inspire more users to create their own Bitmoji lookalike.

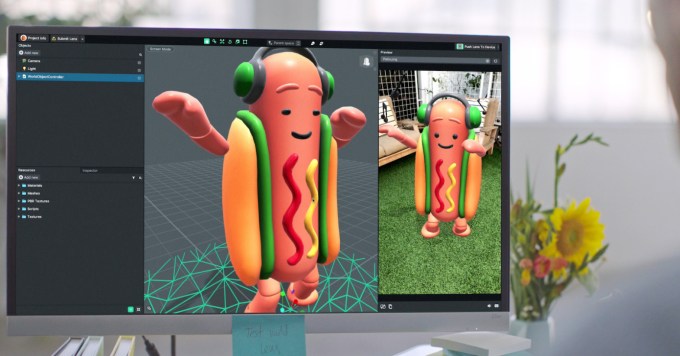

Snapchat is also working on a way for developers to integrate its editing tool-laden and AR-equipped camera into their own apps. Instead of having to reinvent the wheel if they want to permit visual sharing and inevitably building a poor knockoff, apps could just add Snapchat’s polished camera. The idea is the photos and videos shot with the camera could then be used in that app as well as shared back to Snapchat. Similar to Facebook and Instagram Stories opening up to posts from third-parties, this could inject fresh forms of content into Snapchat at a time when usage is slipping.

Launching a platform also means Snapchat will take on new risks, as third-parties with access to user data could be breached. Snap will also have to convince developers that making it easier for its 191 million daily users to join their apps is worth the engineering resources, given how that community is dwarfed by the multi-billion user Google and Facebook login systems.

Snapchat has struggled to get out of Facebook’s shadow despite inventing or acquiring what would become some of the hottest trends in social. Yet Snap Inc could develop alliances with a platform that leverages its differentiators — a teen audience that doesn’t care for Facebook, inherent privacy, and custom avatars. Through an army of developers, Snapchat might find the firepower to challenge the blue empire.

For more on Snapchat and its competitors, check out our other coverage:

China’s “social credit” system is not actually, the students argued, absolutely unethical — that judgment involves a certain amount of cultural bias. But I’m comfortable putting it here because of the massive ethical questions it has sidestepped and dismissed on the road to deployment. Their highly practical suggestions, however, were focused on making the system more accountable and transparent. Contest reports of behavior, see what types of things have contributed to your own score, see how it has changed over time, and so on.

China’s “social credit” system is not actually, the students argued, absolutely unethical — that judgment involves a certain amount of cultural bias. But I’m comfortable putting it here because of the massive ethical questions it has sidestepped and dismissed on the road to deployment. Their highly practical suggestions, however, were focused on making the system more accountable and transparent. Contest reports of behavior, see what types of things have contributed to your own score, see how it has changed over time, and so on.