“The percentage of Top 40 music made with our platform blows my mind” says Splice co-founder Steve Martocci. He tells me about some bedroom music producers who were “working at Olive Garden until they put sounds on Splice.” Soon they quit their jobs since they were earning enough from artists downloading those sounds to use in their songs. That led them to collaborate with famous DJ Zedd, resulting in the Billboard #12 hit “Starving”.

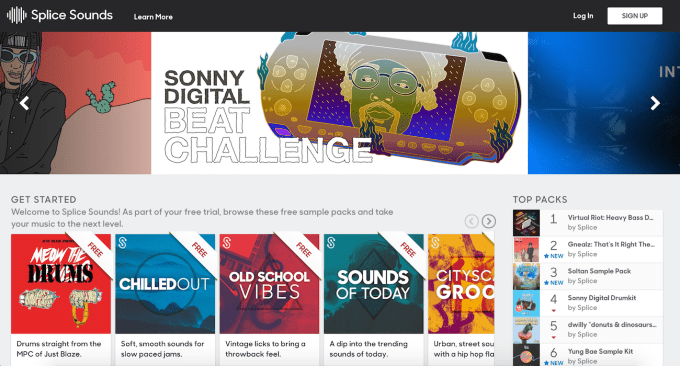

Splice has attracted $47 million in funding to power this all-new music economy. That might be a shock considering Martocci estimates that 95% of digital instruments and sample packs are pirated since they’re often expensive with no try-before-you-buy option. Even Kanye West got caught stealing the trendy Serum digital synthesizer.

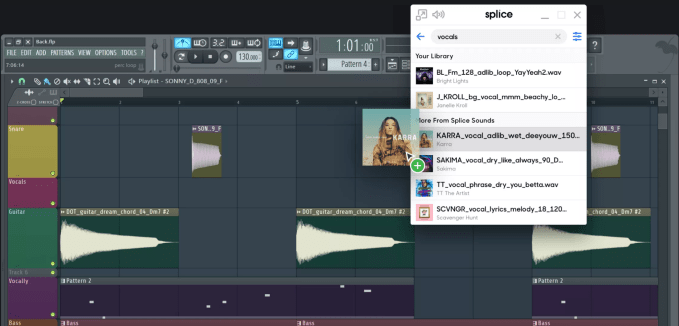

But Splice lets artists pay $7.99 per month to download up to 100 samples they can use royalty-free to create music. That’s cheaper than it costs to listen to music on Spotify. Splice then compensates artists based on how frequently their sounds are downloaded, and has already paid out over $7 million.

Splice Sounds is like an iTunes Store for samples

“We try to make more seats at the table in the music business” says Martocci, who previously founded messaging app GroupMe which sold to Skype for between $50 million and $80 million in 2011. “GroupMe was made to go to concerts with our friends. Music has always been my motivator, but code is my canvas. Artists come up to me and hug me because I’m changing the creative process.”

Splice co-founder Steve Martocci

But now he’s getting some big name assistance, attracted by Splice’s success in the stubborn musician community and its $35 million Series B from December. Splice has just hired former Facebook product manager Matt Pake as VP of product to lead core teams in New York, and former Secret co-founder Chrys Bader to build out a new squad in Los Angeles. [Disclosure: I knew both from before they moved out of the SF social scene]

Splice now has 100 staffers, mostly hobbyist musicians themselves, but “I don’t think I have one bay area employee” says Martocci. He wants his offices where the artists live. “Everyone has a genuine passion for music. It doesn’t feel like a tech company as much” says Bader. Martocci apparently takes feedback well, which is different because “I’ve had some pretty fucking hard people to work with in the past…” Bader notes, likely referring to disagreements with his co-founder at Secret. “I have zero tolerance for bullshit at this point in my life and there’s zero bullshit on this team.”

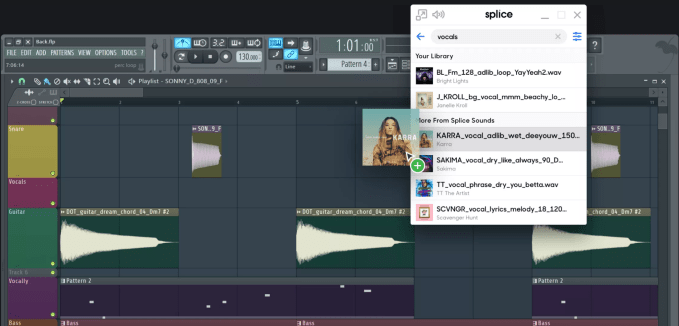

While the Sounds marketplace has blown up recently, pushing Splice to 1.5 million users, the startup has a grander vision for software to eat instruments. That means creating the same kind of tools that help programmers code apps, but for musicians to compose songs. Splice Studio integrates with composition software like GarageBand, Logic, and Ableton to offer cloud-synced version control.

This might sound nerdy, but it’s a lifesaver. Splice Studio automatically backs up the artist’s work-in-progress song after every single edit so they can always reverse changes and safely work with collaborators without having to nervously save manually and fret about keeping all the copies organized.

Splice saves every edit to a song-in-progress so you can experiment but always reverse changes

Since Splice’s staffers actually make music themselves rather than parachuting into a foreign space, they intimately understand the frustrations they’re trying to solve. Knowing income can be unpredictable, Splice lets musicians access plugins, software, and instruments on a rent-to-own basis where they can pause payment and resume later. That’s the kind of convenience that Bader says makes Splice “easier than piracy”, echoing Spotify director Sean Parker’s plan to beat bootleg MP3s with a simple streaming service. “I wanted to build something even Reddit couldn’t complain about”, Martocci laughs.

But where Splice goes next could addresses the biggest, most insidious barrier to creative output: writer’s block. Ask most modern musicians, and they’ll tell you about their giant folders of unfinished songs. Getting from a melody rattling around in you head to a few tracks laid out in your preferred composition software is the easy part. Polishing those parts, ditching the unnecessary ones, finding the rights sounds, and tieing it all together into something listenable can be agonizingly difficult.

Creative Companion is Splice’s solution. Currently being built by Bader’s LA team, it’s a songwriting assistant that can suggest a next step and surface samples that fit well with those you’re already using. Martocci explains how Splice uses “cool machine learning stuff” to recommend ‘Hey, you should add a bass line. You should add some mastering.”

Splice just hired Chrys Bader, previously the co-founder of Secret

The question for Splice will be how many music producers out there are willing to pay. “There’s an upper bound. This is not a consumer product” Bader admits. Citing internal research, he says there 30 million music producers in the world. Many might not even know about Splice, “but at $8 a month, that’s not really breaking the bank. You might pay $200 for a plugin or $700 for Ableton. That’s insane. Musicans can’t afford that. Yet a musician friend tells me all the time ‘I’m broke, I’m broke…but I live or die by Splice.'”

Splice’s heavy-duty funding from Union Square Ventures, True Ventures, and DFJ could also attract competition. It might awake the interest of big creative services corporations like Adobe, or more established music production tool companies like Native Instruments which just launched a direct competitor called Sounds.com. But Splice is digging in for a long fight, giving away Splice Studio to lure in users and commissioning exclusive sample packs from top creators. In that sense, Splice is almost like a record label.

“I want to see a world with more transcendent musical highs” where “you have more music that’s ready for moment” Martocci opines. “If we build something that makes musicians lives better, that makes our lives better because a lot of us are musicians, what else is there in life?” Bader explains.

“I want to see a world with more transcendent musical highs” where “you have more music that’s ready for moment” Martocci opines. “If we build something that makes musicians lives better, that makes our lives better because a lot of us are musicians, what else is there in life?” Bader explains.

Computers democratized music-making, leading to a flood of amateurs sharing their content with the world. But all good democratizations necessitate layers of curation to sort through all the output, which social networks have become, and tools to let the most talented artists create what’s worth everyone’s attention.

Martocci concludes “Software is a great instrument. One-third of the world tries to make music at some point. They’re not going to pick up guitars and recorders any more.” Whatever app they choose, Splice wants to keep them in the creative flow.

“I want to see a world with more transcendent musical highs” where “you have more music that’s ready for moment” Martocci opines. “If we build something that makes musicians lives better, that makes our lives better because a lot of us are musicians, what else is there in life?” Bader explains.

“I want to see a world with more transcendent musical highs” where “you have more music that’s ready for moment” Martocci opines. “If we build something that makes musicians lives better, that makes our lives better because a lot of us are musicians, what else is there in life?” Bader explains.