Photo courtesy of Shutterstock/Brian A. Jackson

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock/Brian A. Jackson

My HomePod, Google Home and Amazon Echo all live within about 15 feet of each other in my apartment.

This is as much a testament to my obsession with smart home crap as it is to my inability to buy into a single tech giant’s hardware ecosystem. I’ve gone all-in with each assistant at various times but now my entire connected life is run through a series of commands that are held together by specific intonations, exact phrasing and speaking volumes of which I alone fully grasp. I solely hold the recipes to my MacGyvered connected life. (This has made life difficult for my roommate who sometimes has to ask me to turn the lights on, but truthfully he should have known what annoying techiness laid ahead when he saw me unpacking my VR rig as we moved in.)

This amalgam of chatty smart assistants has made me pretty in tune with each of these product’s faults, but it’s also helped me gain a deep appreciation for the individual strengths of the platforms themselves.

This week, Bloomberg reported that times are tough for the HomePod. Apple is cutting production, some of its retail stores aren’t breaking double digit sales of the device on a daily basis and it only has a small sliver of the smart speaker market. This report brought a lot of critics out of the woodwork who heralded the ignorance of Apple’s product strategy and harped on the smart speaker’s general dumbness and lackluster feature set.

Now, I’m not in the habit of defending near-trillion dollar companies, but I think much of this criticism is misplaced. The HomePod is probably the best-functioning smart speaker of the bunch, and I’d also contend that the company’s overall strategy is far from being “years behind” its competitors. Apple’s AI strategy needs some TLC to strengthen Siri, but with the AirPods and HomePod, Apple is building a unified front on audio hardware that will weather the gimmicks of a market that seems artificially mature to begin with.

First off, I’ve always found the “smart speaker market” to be a pie that’s sliced in a bizarre way. For as intimately tied to smartphones as voice assistants are, saying that Amazon remains the clear winner in a category that excludes the billions of mobile devices with deep voice assistant capabilities seems accurate but deeply wrong at the same time.

It’s also why I don’t think Apple needs to be as worried about getting a $50 product like the Home Mini or Echo Dot out there, because while Amazon desperately needs a low-friction connection to consumers, Apple doesn’t gain as much by putting a tinny speaker into a can that will do even less than what “Hey Siri” on your iPhone could do.

$349 is pretty far (too far) in the other direction, but the high-end hardware is the sell for Apple and the concept that consumers are going to default to another smart assistant than what their phone uses is only a problem that will exist in the early days of Siri and Google Assistant. Amazon’s technologies can get better and better but if Google Assistant is the only one with intimate knowledge of your Google Account activities and Siri is the only one that you can send iMessages with, there’s not much of a conversation to have.

The dumbest answer from a smart speaker is always the one you’re waiting on that never comes. Just as the Airpods have succeeded in their approach thanks to the less sexy connectivity advances, the HomePod wins on the intelligence of its listening capabilities via a microphone array that can hear me at a whisper’s volume even while loud music is playing. It’s an overlooked feature in hardware comparisons, and it’s honestly one of the most important in practice.

I’ve yelled so many “Hey Google’s” while the TV is playing that never registered. Meanwhile, I’ve learned that I don’t really have to raise my voice to talk with the HomePod. That, along with its much blogged-about location-aware features of the HomePod, make it a device that feels like more of an ethereal presence in my apartment and less tied down to a physical location where I point my head and yell. While Amazon’s tech here has long been impressive as well, I’ve found the HomePod to be a bit more effective when tunes are blaring while pretty much laying waste to Google’s smart speakers (including the Max) which have always seemed to be hard of hearing in noisy environments from my experience.

Now, Siri is absolutely less good than Google Assistant when it comes to being a phone assistant, but a lot of these shortcomings don’t translate as jarringly to the HomePod. Apple has made the wrong calls with third party integrations for Siri on iOS but the current state of Alexa Skills and Google Assistant Actions suggests that Apple isn’t missing a ton on the smart speaker third-party platform front yet.

Something like ordering a pizza with Domino’s on an Echo or Google Home requires a bizarre amount of effort that is only easy if you do most of the work on your phone ahead of time. I wouldn’t say that Apple missing this feature has torn a hole in its core intelligence, likewise most of these “skills” generally don’t give me the context I need to make a decision.

I don’t get why there’s so much love thrown at these smart speaker development platforms. The fact is, they’re largely outlets for brand marketing budget dollars, rather than bastions of consumer utility. Sure, some of these apps are fun and may ultimately make the Echo a more family-friendly device than the HomePod, but the bloatware eventually becomes an afterthought as the gimmick wears off. Amazon needs this right now, not consumers.

Making calls, distinguishing between multiple users and accessing calendars are all pretty baseline features that one hopes that the HomePod receives updates for soon. Nevertheless, the HomePod is not an unfinished product as some have said, and is certainly not “years behind” its competitors. It certainly feels more finished than some of the hardware products in Amazon’s divergent smart speaker cornucopia.

They’ve made some annoying decisions regarding music streaming support; Apple Music is an absolute necessity to enjoy this product. I’ve been a Spotify listener in the past, but I’ve never been a power user of playlists which left me pretty vulnerable to switching if it made life easier with the HomePod and my AirPods, which it did.

Apple Music is just one more exclusive element of the ecosystem, and by extension, Siri. Despite Spotify’s sky-high market cap, I don’t really see a good reason not to be bullish on Apple Music. The service is rapidly growing and — if trends hold — will overtake Spotify in paid subscriber count sometime this summer. It seems unrealistic that Apple will bring Apple Music support to the Echo or Google Home, but it’d be nice if some skeleton support came to Spotify on HomePod in the meantime, though I kind of doubt this as well.

It’s all about the ecosystem; the “smart speaker market” doesn’t matter and never will as we define it now. What Google gains with a cheap entry point of a Google Home Mini is a way to drive people to features they didn’t know their phones had. Apple is using the HomePod to set a baseline while they look to build up these features that Siri doesn’t have yet. Amazon’s Alexa may have a chance in the context of the connected home, but it’s hard to imagine a world where you don’t want your mobile device and home assistant hub being intimately tied at an OS level.

The AirPods and HomePod are very good examples of OS-integrated hardware, and while Siri needs a facelift and perhaps some brain surgery, Apple’s thinking with the HomePod is about where it needs to be. It’s a platform that should really be a bit experimental for the time-being. These things were pushed into people’s homes so quickly by an Amazonian quest for market domination, but so much of the utility of smart speakers is still tied up in their frustrations.

Like the AirPods, the HomePod has isolated the right challenges to tackle first. “Winning the smart speaker market” isn’t going to happen for this product, but I get a sense that Apple’s thinking with the HomePod is tied up in a healthy self-awareness that its competitors lack.

To: ceo@cybersecuritystartup.com

Subject: Lessons from cybersecurity exits

Dear F0und3r:

What a month this has been for cybersecurity! One unicorn IPO and two nice acquisitions – Zscaler’s great debut on wall street, a $300 million acquisition of Evident.io by Palo Alto Networks and a $350 million acquisition of Phantom Cyber by Splunk has gotten all of us excited.

Word on the street is that in each of those exits, the founders took home ~30% to 40% of the proceeds. Which is not bad for ~ 4 /5 years of work. They can finally afford to buy two bedroom homes in Silicon Valley.

|

Evident.IO Investment Rounds and Return estimates |

||||||

|

Date |

Select Investors |

Round Size |

Pre |

Post |

Dilution |

Estimated Returns / Multiple of Invested Capital |

|

Sep 2013 |

$1.5m |

$5.25m |

$6.75 m |

22% |

44X |

|

|

Nov 2014 |

$9.8 m |

$18.1m |

$28.0 m |

35% |

10.7X |

|

|

Apr 2016 |

$15.7 m |

$35.0 m |

$50.7 m |

30% |

6X |

|

|

Feb 2017 |

GV |

$22.0 m |

$73.6 m |

$95.5 |

23% |

3.1X |

My math is not that good but looks like even some VCs made a decent return. Back of the envelope scribbles indicate that True Ventures scored an estimated ~44X multiple on its seed investment. Others like Bain snagged a ~10X on the A round investment and Venrock which led the Series B round took home ~6X.

We see a similar pattern with Phantom Cyber, which got acquired by Splunk for $350 million. A little bird told me that they had booking in the range of $10 million. But before we all get too self-congratulatory, lets ask – why did these companies sell at $300 million to $350 million when everyone in the valley wants to ride a unicorn? Clearly, funds like GV, Bain and Kleiner could have fueled more rounds to make unicorns out of Evident.io and Phantom Cyber.

|

Phantom Cyber Investment Rounds and Return estimates |

||||||

|

Date |

Select Investors |

Round Size |

Pre |

Post |

Dilution |

Estimated Returns / Multiple of Invested Capital |

|

April 2015 |

Foundation Capital |

$2.7m |

$8.3 m |

$11.04 m |

14.50% |

31.7 |

|

Sep 2015 |

Blackstone |

$6.5m |

$26.7 m |

$33.2 m |

15.90% |

10.5 |

|

Jan 2017 |

KPCB |

$13.5m |

$83.0 m |

$96.5 m |

13.90% |

3.6 |

(Data Source: Pitchbook)

Some of the board members might have peeked at the exit data gathered by the hardworking analysts at Momentum Cyber, a cybersecurity advisory firm. Look at security exit trends from 2010-2017. You might notice that ~68% of security exits were below $100 million. And as much as 85% of exits occur below $300 million.

Agreed that there are very few exceptional security CEO’s like Jay Chaudhry who grew up in a Himalayan village, and led ZScaler to an IPO. This was Jay’s fifth startup and he kept over 25.5% of the proceeds, with another 28.3% owned by his trust. TPG Growth owned less than 10%. After all, he himself funded a substantial part of the company (which raised a total of $110 million). But not everyone is as driven, successful and it’s ok to sell if the exit numbers are meaningful. Remember what that bard of avon once said:

For I must tell you friendly in your ear,

Sell when you can; you are not for all markets.

(Shakespeare, As you Like It, Act 3, Scene V)

(68% of security exits occur below $100 million. M & A Data from 2010-2017. Source: Momentum Cyber)

My friend Dino Boukouris, a director at Momentum Cyber, offers some sage advice to all founders who are smitten by unicorns. “Before a founder raises their next round, I would reflect on the market’s ability to purchase companies. The exit data says it all. As you raise more capital, your exit value goes up, timing gets stretched and the number of buyers who can afford you drops.” Dino has a point, you see. As we inflate valuations, your work, my dear CEO, becomes much harder.

If you don’t believe Dino, let’s look at another recent exit, PhishMe, which was acquired by a private equity consortium for $400 million. That’s a nice number, correct? At the first look, you’ll notice that the dilution and financial return patterns are similar to that of Phantom. Except that PhishMe took 7 years and consumed $58 million of capital, while Phantom took 3 years and consumed $22.7 million. Timing and capital efficiency matter as much as exit value. It’s not just the exit value ~ but how long and how much. Back to my man, Dino who will gently remind you that for the 175 M & A transactions in 2017, the median value was $68 milion. Read that last sentence again — very slowly. $68 million. Ouch!

|

PhishMe Investment Rounds |

||||||

|

Date |

Round size |

Select Investors |

Pre-money Valuation |

Post |

Dilution |

Returns / Multiple of Invested Capital |

|

July 2012 |

$2.5m |

Paladin |

$10 m |

12.5 m |

12.20% |

32.0 |

|

March 2015 |

$13 m |

Paladin |

$61 m |

$74 m |

13 % |

5.4 |

|

July 2016 |

$42.5 m |

Bessemer |

$155 m |

197 m |

21% |

2.0 |

(Data Source: Pitchbook)

Two years ago in Cockroaches versus Unicorns – The Golden Age of Cybersecurity Startups cybersecurity founders were urged to avoid the unicorn hubris. A lot of bystanders, your ego included, will cheer you as you get higher valuations. But aren’t we all rational human beings, always making data based decisions?

Marc Andreessen will remind you that his best friend, Jim Barksdale, once said “If we have data, let’s look at data. If all we have are opinions, let’s go with mine.” Since 2012, my VC friends have funded 1242 cybersecurity companies, investing a whopping $17.8bn. But chief information security officers say that they don’t need 1242 security products. One exhausted CISO told me they get fifteen to seventeen cold calls a day. They hide away from LinkedIn, being bombarded relentlessly.

Enrique Salem (former CEO of Symantec) and Noah Carr, both with Bain Capital are celebrating the successful sale of Evident.io. They pointed out that the founders — Tim Prendergast and Justin Lundy had lived the public cloud security problem in their previous lives at Adobe. “Such deep domain expertise allowed them to gain credibility in the market. It’s not easy to earn the trust of their customers. But given their strong engineering team, they were able to build an “easy to deploy” solution that could scale to customers with 1000s of AWS / Azure accounts. Customers were more willing to be reference-able, given this aligned relationship.”

(Source: Momentum Cyber)

You, my dear CEO, should take a page from that playbook. Because Jake Flomenberg, Partner at Accel Partners says, “CISOs are suffering from indigestion. They are looking to rationalize toolsets and add very selectively. New layer X for new threat vector Y is an increasingly tough sell.” According to Cack Wilhelm Partner at Accomplice, “Security analysts have alert fatigue, and CISOs have vendor fatigue.” You are one of those possibly, wouldn’t you agree?

Besides indigestion and fatigue, the CISO roles have become demanding. William Lin, Principal at Trident Capital Cyber, a $300m fund pointed out that “the role of CISO has bifurcated into managing risk akin to an auditor and at the same time, managing complex engineering and technology environments.” So naturally, they are managing their time more cautiously and not looking forward to meeting one more startup.

Erik Bloch, Director of Security Products at SalesForce says that while he keeps an open mind and is willing to look at innovative startups, it takes him weeks to arrange calls with the right people, and months to scope a POC. And let’s not forget the mountain of paperworks and legal agreements. “It’s great to say you have a Fortune 100 as an early customer, but just be warned that it’ll be a long, hard road to get there, so plan appropriately” he pointed out.

So, my dear founder, as the road gets harder, funding slows down. Look at 2017 — despite all those big hacks, Series A funding dropped by 25% in 2017. Clearly, many of our seed funded companies are not delivering those Fortune 100 POC milestones. And are unable to raise a Series A. Weep, if we must, but let us remind ourselves that out point solutions are not that impressive to the CISOs.

All the founders I know are trying to raise a formulaic $8m Series A on $40m pre. But not every startup that wants 8 on 40 deserves it. Revenues and growth rate, those quaint metrics matter more than ever. And some investors look for the quality of your customers. Aaron Jacobson of NEA, a multi-billion dollar venture fund says, ”A key value driver is a thought-leader CISO as a customer. This is often a good indicator of value creation.“

|

Stage |

Expected Revenue Run Rate |

Estd. Round Size |

|

Angel |

None |

Up to $2m |

|

Series A |

$1.5m to $3 m |

$5m to $8m |

|

Early VC |

$5 m to $8 m |

$15m to $25m |

|

Late Stage VC |

$6m to $10m |

$30m to $50m |

When markets get crowded and all startups sound the same, investors seek quality, or move to later stages. They like to see well proven companies, that have solved a lot of basic problems. And eliminated riskier stumbling blocks. Like product-market fit, pricing and go-to-market issues. Naturally, the later stage valuations are rising faster. Money is chasing quality, growth and returns.

Median Post-Money Valuation by stage for cybersecurity companies (Source: Pitchbook)

The security IPOs offer a sobering view. This is a long journey, not for the faint of heart. Okta moved fast, consumed ~4X more capital as compared to Sailpoint and delivered great returns.

|

Company |

Year Founded |

Years to IPO |

Total Capital raised prior to IPO |

Revenues (2017) |

Post Money of last round prior to IPO |

Market Cap at IPO |

|

ZScaler |

2008 |

10 |

$180m |

$176 m |

$1.05 bn |

$3.6 bn |

|

Okta |

2009 |

8 |

$231 m |

$160 m |

$1.18 bn |

$2.1 bn |

|

Forescout |

2000 |

17 |

$159 m |

$220 m |

$1.0 bn |

$806 mn |

|

SailPoint |

2004 |

13 |

$54.7 m |

$186 m |

N/A |

$1.1 bn |

Security IPOs (Source: Momentum Cyber, Pitchbook)

Innovating with go-to-market strategies

In the near term, the big challenge for you, dear security founder, is selling in an over crowded market. If I were you, I’d remember that innovation should not be restricted to merely technology, but can extend into sales and marketing. We lack creativity when it comes to marketing – ask Kelly Shortridge of Security ScoreCard. She should get some kind of BlackHat award for developing this godforsaken Infosec Startup Bingo. If you find any startup vendor that uses all these words, and wins this bingo, please DM me ~ I will promptly shave my head in shame. We got here because we do not possess simple marketing muscles. We copy each other while our customers roll their eyes when we pitch them.

Sid Trivedi of Omidyar Technology Ventures wants to work with the developer focussed startups. He says, “Look at companies like Auth0. The sales efficiency on developer-focused platforms is tremendous. You can go to a CISO, CIO or CTO and point out that X number of developers are paying to use my technology. Here are their names, why don’t you talk to them? And then, let’s discuss an enterprise license for the full company?” That approach works like magic. Overwhelming majority of the software IPOs like Twilio, Mulesoft, SendGrid are developer platforms.”

If you go top-down in a hurry, you can crash and burn. I am aware of an impatient security vendor who used executive level pressure at a Fortune 50 company. They kicked their way into the POC. And got kicked out by the infosec team. The furios infosec team destroyed the vendor in a technical assessment. I was told that the product was functional but the vendor’s impatience and political gymnastics killed the deal. Let us not forget simple truth: many times CISOs turn to their subordinates for advice and decision-making, so don’t just sell to the top. Nor ignore the rest of the people in the room.

With more noise, the buyers freeze. Margins shrink. Revenues and growth slows down. Which means it’s harder to get to your milestones before your next round. Running out of cash is not fun. Nor is a down round, layoffs and such. So while this is easier said than done, please raise less and do more. And maybe, just maybe, you can keep 40% of a $350 million exit.

If you have questions or existential dilemmas, you can always find me, chatting with a friendly VC in South Park. Or I’m always around in a trusted secure world of Signal.

Stay safe at that annual security stampede called RSA.

Kindly,

Mahendra

PS: Let’s not forget to express our gratitude to those analysts at Momentum Cyber and Pitchbook for painstakingly tracking every investment, analyzing and presenting meaningful data. They help us look at the forest, and make our journey easier. Send them a thank-you tweet, some wine, chocolates, flowers or home-baked cookies.

Outrage that Facebook made the private data of over 87 million of its U.S. users available to the Trump campaign has stoked fears of big US-based technology companies are tracking our every move and misusing our personal data to manipulate us without adequate transparency, oversight, or regulation.

These legitimate concerns about the privacy threat these companies potentially pose must be balanced by an appreciation of the important role data-optimizing companies like these play in promoting our national security.

In his testimony to the combined US Senate Commerce and Judiciary Committees, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was not wrong to present his company as a last line of defense in an “ongoing arms race” with Russia and others seeking to spread disinformation and manipulate political and economic systems in the US and around the world.

The vast majority of the two billion Facebook users live outside the United States, Zuckerberg argued, and the US should be thinking of Facebook and other American companies competing with foreign rivals in “strategic and competitive” terms. Although the American public and US political leaders are rightly grappling with critical issues of privacy, we will harm ourselves if we don’t recognize the validity of Zuckerberg’s national security argument.

Facebook CEO and founder Mark Zuckerberg testifies during a US House Committee on Energy and Commerce hearing about Facebook on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, April 11, 2018. (Photo: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images)

Examples are everywhere of big tech companies increasingly being seen as a threat. US President Trump has been on a rampage against Amazon, and multiple media outlets have called for the company to be broken up as a monopoly. A recent New York Times article, “The Case Against Google,” argued that Google is stifling competition and innovation and suggested it might be broken up as a monopoly. “It’s time to break up Facebook,” Politico argued, calling Facebook “a deeply untransparent, out-of-control company that encroaches on its users’ privacy, resists regulatory oversight and fails to police known bad actors when they abuse its platform.” US Senator Bill Nelson made a similar point when he asserted during the Senate hearings that “if Facebook and other online companies will not or cannot fix the privacy invasions, then we are going to have to. We, the Congress.”

While many concerns like these are valid, seeing big US technology companies solely in the context of fears about privacy misses the point that these companies play a far broader strategic role in America’s growing geopolitical rivalry with foreign adversaries. And while Russia is rising as a threat in cyberspace, China represents a more powerful and strategic rival in the 21st century tech convergence arms race.

Data is to the 21st century what oil was to the 20th, a key asset for driving wealth, power, and competitiveness. Only companies with access to the best algorithms and the biggest and highest quality data sets will be able to glean the insights and develop the models driving innovation forward. As Facebook’s failure to protect its users’ private information shows, these date pools are both extremely powerful and can be abused. But because countries with the leading AI and pooled data platforms will have the most thriving economies, big technology platforms are playing a more important national security role than ever in our increasingly big data-driven world.

BEIJING, CHINA – 2017/07/08: Robots dance for the audience on the expo. On Jul. 8th, Beijing International Consumer electronics Expo was held in Beijing China National Convention Center. (Photo by Zhang Peng/LightRocket via Getty Images)

China, which has set a goal of becoming “the world’s primary AI innovation center” by 2025, occupying “the commanding heights of AI technology” by 2030, and the “global leader” in “comprehensive national strength and international influence” by 2050, understands this. To build a world-beating AI industry, Beijing has kept American tech giants out of the Chinese market for years and stolen their intellectual property while putting massive resources into developing its own strategic technology sectors in close collaboration with national champion companies like Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent.

Examples of China’s progress are everywhere.

Close to a billion Chinese people use Tencent’s instant communication and cashless platforms. In October 2017, Alibaba announced a three-year investment of $15 billion for developing and integrating AI and cloud-computing technologies that will power the smart cities and smart hospitals of the future. Beijing is investing $9.2 billion in the golden combination of AI and genomics to lead personalized health research to new heights. More ominously, Alibaba is prototyping a new form of ubiquitous surveillance that deploys millions of cameras equipped with facial recognition within testbed cities and another Chinese company, Cloud Walk, is using facial recognition to track individuals’ behaviors and assess their predisposition to commit a crime.

In all of these areas, China is ensuring that individual privacy protections do not get in the way of bringing together the massive data sets Chinese companies will need to lead the world. As Beijing well understands, training technologists, amassing massive high-quality data sets, and accumulating patents are key to competitive and security advantage in the 21st century.

“In the age of AI, a U.S.-China duopoly is not just inevitable, it has already arrived,” said Kai-Fu Lee, founder and CEO of Beijing-based technology investment firm Sinovation Ventures and a former top executive at Microsoft and Google. The United States should absolutely not follow China’s lead and disregard the privacy protections of our citizens. Instead, we must follow Europe’s lead and do significantly more to enhance them. But we also cannot blind ourselves to the critical importance of amassing big data sets for driving innovation, competitiveness, and national power in the future.

UNITED STATES – SEPTEMBER 24: Aerial view of the Pentagon building photographed on Sept. 24, 2017. (Photo By Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call)

In its 2017 unclassified budget, the Pentagon spent about $7.4 billion on AI, big data and cloud-computing, a tiny fraction of America’s overall expenditure on AI. Clearly, winning the future will not be a government activity alone, but there is a big role government can and must play. Even though Google remains the most important AI company in the world, the U.S. still crucially lacks a coordinated national strategy on AI and emerging digital technologies. While the Trump administration has gutted the white house Office of Science and Technology Policy, proposed massive cuts to US science funding, and engaged in a sniping contest with American tech giants, the Chinese government has outlined a “military-civilian integration development strategy” to harness AI to enhance Chinese national power.

FBI Director Christopher Wray correctly pointed out that America has now entered a “whole of society” rivalry with China. If the United States thinks of our technology champions solely within our domestic national framework, we might spur some types of innovation at home while stifling other innovations that big American companies with large teams and big data sets may be better able to realize.

America will be more innovative the more we nurture a healthy ecosystem of big, AI driven companies while also empowering smaller startups and others using blockchain and other technologies to access large and disparate data pools. Because breaking up US technology giants without a sufficient analysis of both the national and international implications of this step could deal a body blow to American prosperity and global power in the 21st century, extreme caution is in order.

America’s largest technology companies cannot and should not be dragooned to participate in America’s growing geopolitical rivalry with China. Based on recent protests by Google employees against the company’s collaboration with the US defense department analyzing military drone footage, perhaps they will not.

But it would be self-defeating for American policymakers to not at least partly consider America’s tech giants in the context of the important role they play in America’s national security. America definitely needs significantly stronger regulation to foster innovation and protect privacy and civil liberties but breaking up America’s tech giants without appreciating the broader role they are serving to strengthen our national competitiveness and security would be a tragic mistake.

Would being asked to pay Facebook to remove ads make you appreciate their value or resent them even more? As Facebook considers offering an ad-free subscription option, there are deeper questions than how much money it could earn. Facebook has the opportunity to let us decide how we compensate it for social networking. But choice doesn’t always make people happy.

In February I explored the idea of how Facebook could disarm data privacy backlash and boost well-being by letting us pay a monthly subscription fee instead of selling our attention to advertisers. The big takeaways were:

However, my analysis neglected some of the psychological fallout of telling people they only get to ditch ads if they can afford it, the loss of ubiquitous reach for advertisers, and the reality of which users would cough up the cash. Though on the other hand, I also neglected the epiphany a price tag could produce for users angry about targeted advertising.

This conversation is relevant because Zuckerberg was asked twice by congress about Facebook potentially offering subscriptions. Zuckerberg endorsed the merits of ad-supported apps, but never ruled out letting users buy a premium version. “We don’t offer an option today for people to pay to not show ads” Zuckerberg said, later elaborating that “Overall, I think that the ads experience is going to be the best one. I think in general, people like not having to pay for a service. A lot of people can’t afford to pay for a service around the world, and this aligns with our mission the best.”

But that word ‘today’ gave a glimmer of hope that we might be able to pay in the future.

Facebook CEO and founder Mark Zuckerberg testifies during a US House Committee on Energy and Commerce hearing about Facebook on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, April 11, 2018. (Photo: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images)

What would we be paying for beyond removing ads, though?. Facebook already lets users concerned about their privacy opt out of some ad targeting, just not seeing ads as a whole. Zuckerberg’s stumping for free Internet services make it seem unlikely that Facebook would build valuable features and reserve them for subscribers

Spotify only lets paid users play any song they want on-demand, while ad-supported users are stuck on shuffle. LinkedIn only lets paid users message anyone they want and appear as a ‘featured applicant’ to hirers, while ad-supported users can only message their connections. Netflix only lets paid users…use it at all.

But Facebook views social networking as a human right, and would likely want to give all users any extra features it developed like News Feed filters to weed out politics or baby pics. Facebook also probably wouldn’t sell features that break privacy like how LinkedIn subscribers can see who visited their profiles. In fact, I wouldn’t bet on Facebook offering any significant premium-only features beyond removing ads. That could make it a tough sell.

But Facebook views social networking as a human right, and would likely want to give all users any extra features it developed like News Feed filters to weed out politics or baby pics. Facebook also probably wouldn’t sell features that break privacy like how LinkedIn subscribers can see who visited their profiles. In fact, I wouldn’t bet on Facebook offering any significant premium-only features beyond removing ads. That could make it a tough sell.

Meanwhile, advertisers trying to reach every member of a demographic might not want a way for people to pay to opt-out of ads. If they’re trying to promote a new movie, a restaurant chain, or an election campaign, they’d want as strong of penetration amongst their target audience as they can get. A subscription model punches holes in the ubiquity of Facebook ads that drive businesses to the app.

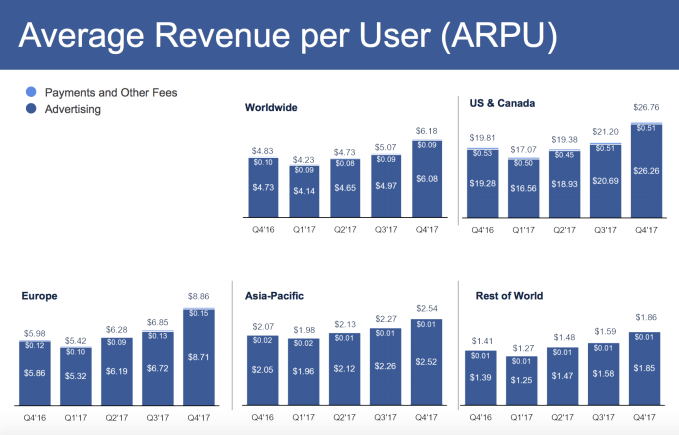

But the biggest issue is that Facebook is just really good at monetizing with ads. For never charging users, it earns a ton of money. $40 billion in 2017. Convincing people to pay more with their wallets than their eyeballs may be difficult. And the ones who want to pay are probably worth much more than the average.

Let’s look at the US & Canada market where Facebook earns the most per user because they’re wealthier and have more disposable income than people in other parts of the world, and therefore command higher ad rates. On average US and Canada users earn Facebook $7 per month from ads. But those willing and able to pay are probably richer than the average user, so luxury businesses pay more to advertise to them, and probably spend more time browsing Facebook than the average user, so they see more of those ads.

Brace for sticker shock, because for Facebook to offset the ad revenue of these rich hardcore users, it might have to charge more like $11 to $14 per month.

With no bonus features, that price for something they can get for free could seem way too high. Many who could afford it still wouldn’t justify it, regardless of how much time they spend on Facebook compared to other media subscriptions they shell out for. Those who truly can’t afford it might suddenly feel more resentment towards the Facebook ads they’ve been scrolling past unperturbed for years. Each one would be a reminder that they don’t have the cash to escape Facebook’s data mines.

But perhaps it’s just as likely that people would feel the exact opposite — that having to see those ads really isn’t so bad when faced with the alternative of a steep subscription price.

People often don’t see worth in what they get for free. Being confronted with a price tag could make them more cognizant of the value exchange they’re voluntarily entering. Social networking costs money to operate, and they have to pay somehow. Seeing ads keeps Facebook’s lights on, its labs full of future products, and its investors happy.

That’s why it might not matter if Facebook can only get 4 percent, or 1 percent, or 0.1 percent of users to pay. It could be worth it for Facebook to build out a subscription option to empower users with a sense of choice and provide perspective on the value they already receive for free.

For more big news about Facebook, check out our recent coverage:

Few Facebook critics are as credible as Roger McNamee, the managing partner at Elevation Partners. As an early investor in Facebook, McNamee was only only a mentor to Mark Zuckerberg but also introduce him to Sheryl Sandberg.

So it’s hard to underestimate the significance of McNamee’s increasingly public criticism of Facebook over the last couple of years, particularly in the light of the growing Cambridge Analytica storm.

According to McNamee, Facebook pioneered the building of a tech company on “human emotions”. Given that the social network knows all of our “emotional hot buttons”, McNamee believes, there is “something systemic” about the way that third parties can “destabilize” our democracies and economies. McNamee saw this in 2016 with both the Brexit referendum in the UK and the American Presidential election and concluded that Facebook does, indeed, give “asymmetric advantage” to negative messages.

McNamee still believes that Facebook can be fixed. But Zuckerberg and Sandberg, he insists, both have to be “honest” about what’s happened and recognize its “civic responsibility” in strengthening democracy. And tech can do its part too, McNamee believes, in acknowledging and confronting what he calls its “dark side”.

McNamee is certainly doing this. He has now teamed up with ex Google ethicist Tristan Harris in the creation of The Center for Human Technology — an alliance of Silicon Valley notables dedicated to “realigning technology with humanity’s best interests.”

Although some colleges may offer a major program in business or entrepreneurship, there isn’t exactly a major in venture capital or angel investment.

Crunchbase News has already examined where professional VCs and angel investors went to college (yes, there’s some truth to the Harvard and Stanford stereotypes) and when having an MBA matters in the world of entrepreneurial finance. But we haven’t yet looked at one facet of startup investors’ educational backgrounds: what they studied in college. So that’s what we’re going to dive into today.

To accomplish this, we’re going to use the educational histories from nearly 5,000 VC American and Canadian investment partners (e.g. folks who are employed by and invest on behalf of a venture capital firm) and nearly 8,500 angel investors in Crunchbase. For those with undergraduate degrees (e.g. B.S., B.A., A.B., and all manner of other variations) and majors listed, we then categorized majors into broader fields of study.1

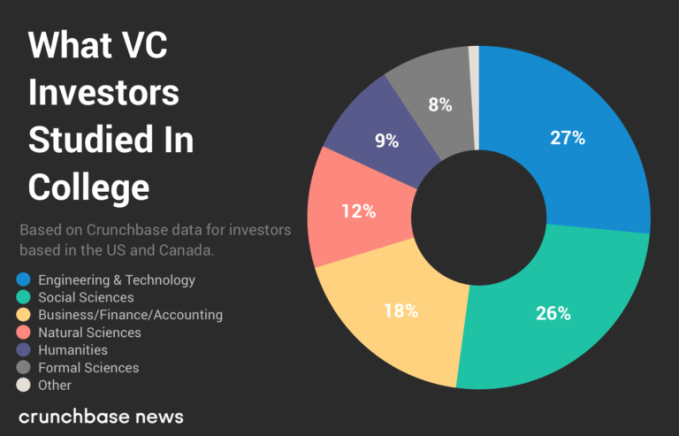

In the chart below, you’ll see a breakdown of professional VCs’ college degrees.

Because startup investors are ostensibly focused on technology companies, the fact that most professional venture capitalists have a background in engineering (electrical, mechanical and industrial engineering mostly, but there are some more niche areas like nuclear engineering represented here) or technical subjects (like information systems and materials science) is predictable.

What might be most interesting here is just how few investment partners majored in formal sciences like math or computer science, ranking lower than the humanities by just a hair.

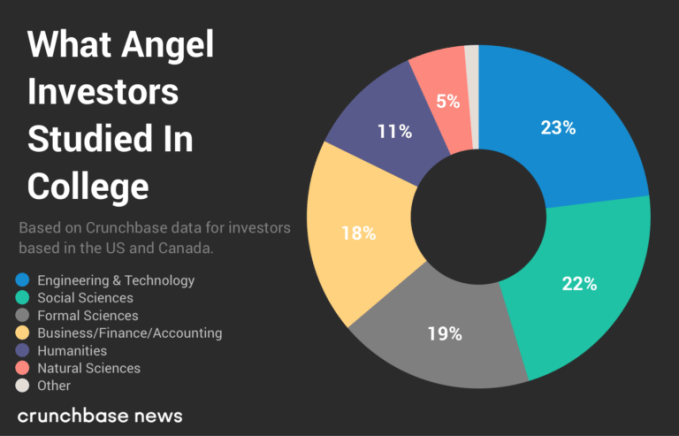

However, this is not the case with angel investors. The chart below displays the breakdown of college degrees for U.S. and Canadian angel investors. It keeps the same color coding as the chart for VCs’ degrees.

Among individual angel investors who are unaffiliated with a venture capital firm, a background in math and computer sciences is more likely.

There are a number of other fun facts to be found in the data:

So what does all of this tell us? At least by our reading, the academic backgrounds of startup investors is quite diverse. And this would make sense. There isn’t a clear career path to becoming a venture capitalist or to having enough money and enthusiasm to make angel investments.

Our first-blush analysis also suggests that folks who studied computer science, mathematics and statistics are potentially under-represented among professional venture capital investors. Considering that many of the startups in which VCs invest are built around a new computing technology on the software or hardware side, this is a rather weird and inexplicable irony.

If you find yourself in college and want to invest in startups someday, either as a professional VC or as an angel investor, study what you want. There’s going to be a lot of other factors besides your undergraduate major that will land you a position in the field.

Silicon Valley is obsessed with unicorns, startups that reach a valuation of $1 billion valuation or more. But Aniyia Williams and her team over at Zebras Unite are more interested in zebras. Unlike unicorns, zebras are real animals. So, when applied to startups, zebras are the ones that bring in actual revenue.

When we talk about the greatest of all time (G.O.A.T.) in tech, it seems only reasonable that it would be a zebra, not necessarily a unicorn. Granted, it could be a zebra-unicorn blend, but it couldn’t be just be a unicorn.

The zebra movement is all-inclusive, Williams told me on an episode of the CTRL+T podcast. That’s regardless of race, gender, sexuality, ability status and so forth. Its focus is on startups building businesses that approach issues from a social impact lens and are focused on generating revenue, she said.

“We are optimizing for profitability over fundability,” Williams said.

We also chatted about Williams’ new organization, Black & Brown Founders, which aims to support black and Latinx founders in tech, and help them to become zebras.

Check it out.

Western airstrikes on the Middle East: déjà vu all over again. Twenty years ago, the USA attacked Sudan and Afghanistan with Tomahawk cruise missiles. Two days ago, the USA attacked Syria with … Tomahawk cruise missiles. Aside from the (de)merits of each attack, isn’t it a bit surprising that technology hasn’t really changed small-scale strategic warfare in that time?

Just you wait. In the next decade, that strategic calculus will change a lot, and probably not in a good way. Consider this sharp one-liner from Kelsey Atherton last week:

Of course cheap drones are already being used on the battlefield in small-scale ways: by Daesh, by Hezbollah, by Hamas, by drug cartels, and of course by traditional nation-state militaries worldwide. But those are piloted drones, used in short-range, often improvisational ways; interesting but not really strategically significant.

Meanwhile, across the world, we are in the midst of a Cambrian explosion of artificial intelligence and automation technology. Consider Comma.ai, the startup that began as a literal one-man self-driving-car project. Consider the truly remarkable Skydio, a self-flying drone that can follow you wherever you go, avoiding obstacles enroute.

…Do you see where we’re going here? Right now only major powers can toss a few explosives at a faraway enemy to drive home a political point. But imagine a flock of bigger Skydios, reprogrammed to fly to certain GPS locations, or certain visual landmarks, or to track certain license plates … while packed full of explosives.

A Tomahawk costs $1.87 million. It seems to me that we are not far at all from the point where a capable and wealthy non-state actor like Daesh, Hezbollah, Hamas, the Sinaloa cartel … or any unsavory group willing to be used for plausible deniability by a nation-state … could build a flock of self-flying targeted kamikaze drones, then smuggle them into the Western destination of their choice, for a lot less than the price of a single Tomahawk. The self-flying and targeting software / AI models won’t need to be nearly as perfect as that of a self-driving car. A 50% failure rate is more than acceptable if you only want to show force and sow panic.

It’s chillingly easy to envision a future of mutual assured terror, a multipolar world in which nations and terror cells and drug cartels and starry-eyed cults alike have the capability to inflict faraway havoc on thousands and constant dread on millions, a smoldering kaleidoscopic landscape of dozens of factions enmeshed in tit-for-tat vengeance and vendettas — ceaseless cycles of sporadic attacks which rarely kill more than a hundred, but send entire populations into perpetual fear and fury. Fury which will be very hard to direct. Like hacking, autonomous drone attacks will be extremely difficult to attribute.

You may call this science-fiction scaremongering, and you may have a point. It’s true that nothing like this has happened yet — though the existing adoption of commercial drones for warfare is a distinct warning sign. It’s true that it would be wrongheaded and ridiculously preemptive to try to slam the barn doors before any drone horses arrive. I’m definitely not suggesting that the West should start thinking about restricting research, or trying to comtrol either hardware or software. (Even if that worked, which it wouldn’t, it would be pointless; drone hardware is cheap, and R&D is global.)

But it’s not too early to start thinking about how we will cope if and when self-flying kamikaze drones do make asymmetric strategic warfare possible. And it’s definitely not too early to try to minimize such warfare before it happens, ideally by actually trying to deal with the root causes of the conflicts burning around the world, rather than lobbing a few cruise missiles their way every time we feel the need to seem particularly outraged. Because one day, not long away at all, that approach will begin to rebound on us disastrously.

The TechCrunch Tel Aviv conference on mobility is in June and we’re excited to announce that Raj Kapoor, the Chief Strategy Officer for Lyft, will be joining as a speaker.

TechCrunch Tel Aviv will focus on mobility and all that it implies, such as autonomous vehicles, drones, you name it.

As well as being the Chief Strategy Officer, he is also the Head of Business for Lyft’s self-driving division. And he also serves as a board advisor for ClassPass, and a Venture Advisor at Mayfield Fund.

Prior to Lyft, Kapoor was a co-founder and CEO of both Snapfish (acquired by HP in 2005) and Fitmob (acquired by ClassPass in 2015), as well as a managing director at Mayfield Fund. Raj holds a BS in Mechanical Engineering and Robotics from Carnegie Mellon University and an MBA from Harvard Business School.

The event will be on June 7, 2018, at the Tel Aviv Convention Center. Israel is one of the world’s fastest growing and most impressive startup ecosystems, and we simply can’t resist coming back. Buy tickets here!