It’s amazing, and yet should surprise no one, that this country’s elected representatives can be either so cynical or so ignorant that two decades into the net neutrality debate, the basics still elude them. Today’s hearing in the House saw Members of Congress airing musty arguments and grandstanding generically as if they had just been informed of the internet this week.

The hearing today at the House Energy and Commerce committee was entitled “Preserving an Open Internet for Consumers, Small Businesses, and Free Speech.” Newly ascended Chairman Frank Pallone (D-NJ), who has been extremely outspoken on these issues for the last few years, gave an introduction that was unmistakably hostile to the present FCC and its replacement of 2015’s net neutrality rules.

The witnesses that would be examined for the next three hours represented both sides of the issue, and it must be said were earnest and well spoken. But the same could not be said for many of the Representatives who were ostensibly there to inform themselves about possibly ways to create federal, bipartisan net neutrality legislation. (You can watch the full hearing here.)

Saying it over and over doesn’t make it any more true

All the old canards were trucked out as if they have not been addressed over and over for years.

The most frequent argument was that Title II, the statutory authority on which the 2015 rules were based (there’s a whole story there if you’re curious), is too old — it was first established in the 1934 Communications Act as a way to regulate interstate communications. Why, these lawmakers asked repeatedly, should we be using rules established in an era when the telegraph and telephone were how people communicated?

The obvious answer we’ve had for years is of course that we don’t; the rules have been updated over and over again to avoid their becoming out of date, though it’s entirely reasonable to suggest we do so again.

Nevertheless, Billy Long (R-MO) wasted everyone’s time with a poorly executed stunt where he had people identify huge photos of recent House Speakers and then brought up Thomas Rainey, the Speaker from 1934. “Even Speaker Rainey would admit that a bill he passed should not be governing this century’s internet,” he ventured. (It’s hard to say. Rainey fast-tracked the entire New Deal and then died in office a month after the Act was passed. He likely would have objected to being used as a prop in this fashion.)

A Representative Soto (R-FL) also made a particular point of how old the law was, suggesting it had last been updated in 1984. Amazingly, he seemed unaware or unwilling to mention the monumental and highly relevant total revisitation of the law that is the 1996 Telecommunications Act.

Only Anna Eshoo (D-CA) seemed to perceive the absurdity of this argument. “A lot of references have been made to old laws. Title II has just been beaten to a pulp. You know what the oldest one is? The constitution. That’s got so much dust on it, maybe we should throw that one out too,” she joked.

But she had her knives out as well, calling out those present for their unconvincing sudden change of heart regarding how important the internet is to their constituents. Nearly everyone who spoke, it must be said, took 30 seconds to a minute of their allotted five to explain for the nth time how precious the internet and freedom of speech on it are.

“Everyone says that they love the internet, how important it is,” Eshoo said. “Where were so many people two years ago, when ripping privacy off the internet went through here like a bolt of lightning? Were you here, Michael? You weren’t here.”

She was referring to the reversal of the Broadband Privacy Rule just after the election, which was a rather nasty piece of work that seemed entirely motivated by industry interests and was widely decried by activists and constituents. It’s a valid question. Who can believe a legislator who says they care if they voted for that repeal? (It’s unclear which Michael she was calling out.)

Not so much a question as a comment…

A few sets of leading questions let the ISP witnesses (Joseph Franell, a very decent-seeming CEO of a rural telecom, and Michael Powell, a canny but likable head of a major trade group NCTA) explain at length how they felt that edge providers like Google and Facebook were the real enemies who were limiting speech on the internet.

That is of course something we should be talking about, and in fact it is an ongoing international discussion. But in the context of a net neutrality debate, it’s a massive red herring.

Net neutrality is about moving bits around without interfering with them, not what businesses like social networks or search providers could or should do with those bits once they have them in their possession.

In the process of these digressions, the telecom CEO admitted that what his company does amounts to being a neutral, purely transmissive party — which is funny considering the FCC makes the opposite assertion in its present rules.

Rep. Johnson (R-OH) rattled off a list of unsubstantiated assertions about the 2015 rules and told Tom Wheeler — who was the FCC Chairman who established those rules — to give a nonsensical yes or no answer and refused to allow him to respond to the “aspersions” he’d just entered into the record. Then he led Franell to say at length that there’s more competition in broadband now than ever, though Franell’s experience as a small rural provider for a few thousand people is hardly representative of the national state of things (being honest, he prefaced his response with this information).

Rep. Flores (R-TX) made a fool of himself by attempting to dispute Mozilla’s statement that it “would not exist today without net neutrality,” pointing out that Mozilla was founded at the turn of the century, and that the net neutrality rules didn’t come around until 2015. This might have been the most frustrating moment of the whole hearing, since it was all at once factually incorrect, ignorant or dismissive of basic context, clearly designed to discredit a witness there in good faith (Mozilla COO Denelle Dixon), and spoken at the end of his allotted time so no response was possible from Dixon.

Luckily Rep. Luján (D-NM) much later generously gave her some time to rebut Flores; she pointed out the obvious fact that 2015 was not the birth of net neutrality, but that the idea of it stretches back decades and fueled the creation and ongoing growth of the Mozilla organization.

Not exactly diamonds but not rough either

A handful of Representatives had specific questions relevant to the creation of future law, if not particularly inspiring ones. It seems clear we’re nowhere near a legislative solution; one Congressman outright said there was no way Trump would sign anything from this Congress.

Congresswoman Matsui (D-CA) inquired about revisions of the Universal Service Fund, a critical budget component for FCC programs that defray the cost of, for example, expanding wireless into rural areas.

Luján questioned FCC Chairman Pai’s assertion that the existing rules would benefit his poorest constituents, saying that was simply not true and that forthcoming laws should be explicit about how they help these communities.

Vermont Democrat Welch pointed out what seemed to be a mismatch between promises that eliminating net neutrality would increase capital expenditure by ISPs and the actual numbers provided by those ISPs. Powell disputed some of these numbers, but the message was clear that economic analysis needs to be far more robust and that hanging a set of rules or laws on broad measures like capex is inadequate justification.

But these small pieces of honest inquiry or criticism produced only a smattering of useful information; the vast majority of the hearing was bloviation and repetition of arguments that have failed to convince anyone for years running. It’s important for us to see this sort of thing, however — it gives faces to the elected officials who bow to industry interests and outright question the need for consumer protections their constituents are calling for.

When you hear that hundreds of lawmakers voted against privacy rules or won’t support net neutrality principles, you often think: “who would do that?” Then you see a hearing like this and you understand: “Oh. That’s who.”

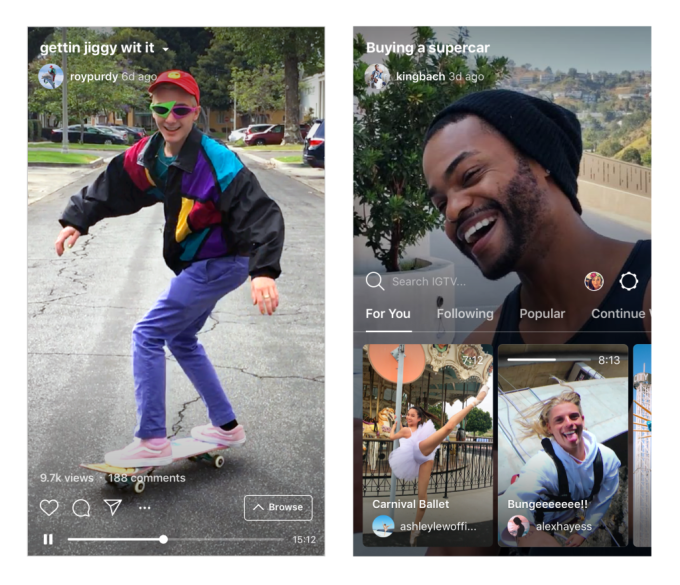

Instagram’s hope was that IGTV would give the company a means of better competing with larger video sites, like Google’s YouTube or Amazon’s Twitch.

Instagram’s hope was that IGTV would give the company a means of better competing with larger video sites, like Google’s YouTube or Amazon’s Twitch. Instagram’s new video initiative also represents another shot across the bow of Instagram purists.

Instagram’s new video initiative also represents another shot across the bow of Instagram purists.