Scott runs operations at

Kruze Consulting, a fast-growing startup CFO consulting firm. Kruze is based in San Francisco with clients in the Bay Area, Los Angeles and New York.

Bill Growney, a partner in Goodwin’s Technology & Life Sciences group, focuses his practice on advising technology and other startup companies through their full corporate life-cycle.

Corporate venture capital (CVC) is booming, with more than $50 billion of CVC capital deployed in 2018. The rise in capital expenditures by CVCs between 2013 and 2018 was an impressive 400%, according to Corporate Venturing Research Data. There are currently more than a hundred active CVC investors, and some sources suggest that almost half of all venture rounds include a strategic investor.

This rise has been driven by two factors: 1) the tech landscape is moving at a faster pace and bigger companies know they need to innovate quicker to meet market demand; and 2) the number of startups seeking CVC capital is growing as founders look beyond traditional venture funds to help grow their businesses.

Kruze Consulting and Goodwin have worked with hundreds of startups through the funding process, including those working with CVCs. Together, the two firms and their principals have decades of experience advising founders during and after their capital raises.

To help startups navigate CVC transactions, we’ve created a guide to working with CVCs. In this segment, we’ll discuss the types of CVCs, the best way to approach each type and the key things to keep in mind during initial discussions.

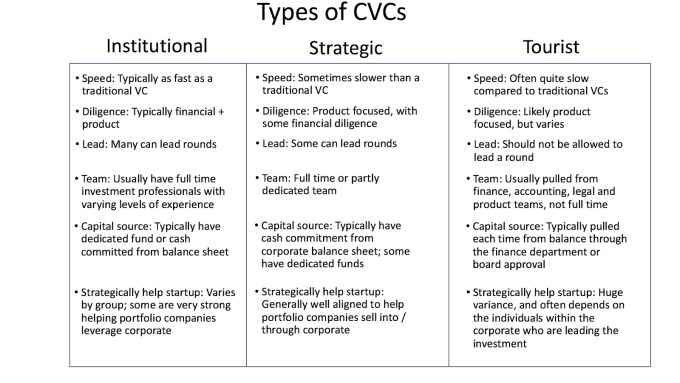

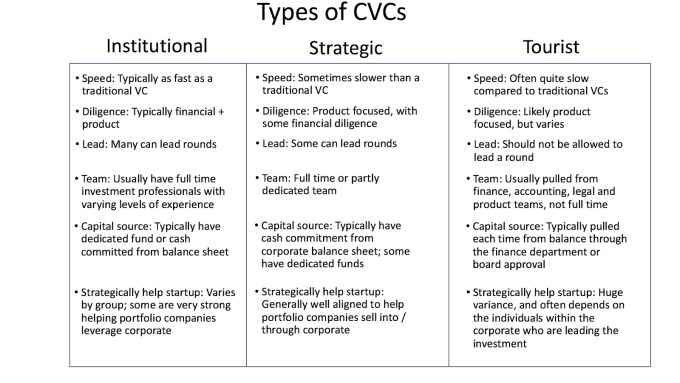

The three types of corporate VCs

Roughly put, CVCs fall into three categories:

- The corporate version of an institutional venture platform, meaning that they look to leverage their parent company’s strategic assets with the goal of scaling their portfolio and driving real revenue. As Grant Allen, general partner at SE Ventures, the CVC arm of Schneider Electric, says, “this type of CVC looks just like a pure financial VC, except with a big company behind them, and the ability to open up real channel revenue.”

- Strategically-minded CVCs are not driven exclusively by returns, but also value innovation. These CVCs are looking for outsourced ways to stay on the leading edge and to learn about new technology that might benefit their parent corporation. This category likely still cares about returns, but their view on ROI is more nuanced than a traditional investor.

- So-called “tourists” often are made up of brand new and relatively inexperienced venture arms of companies that have done very few deals and haven’t had time to develop a strong process or dealflow strategy.

As the realm of CVCs becomes increasingly professionalized, more and more CVCs fall into the first category. For entrepreneurs seeking CVC investors, those in the institutional or strategic category can provide tremendous value — though it’s important that a startup know which type of CVC they’re speaking to, and have clear objectives going in that align with the CVC’s goals and strengths.

Determining which type of CVC you’re dealing with

Before engaging with a CVC, or any potential investor for that matter, the most important step is to do your research. Who is the individual you’re meeting with? What’s his/her background and what deals has he/she done with this venture group? These are Must Knows before walking into the initial meeting.

Once you’re in early discussions, ask the CVC whether he or she has carry in the fund and whether the venture arm is autonomous. The answers to these questions will help you clarify whether you’re dealing with institutional versus strategic CVCs.

“With corporate-backed venture funds, it’s really key up front to know who you’re talking to,” says Allen. “It’s dangerous to call all groups that are nontraditional investors ‘CVCs’ since some are far more serious than others. Most have some degree of strategic mandate but many are increasingly investing for financial gain.”

The next question is: Are you dealing with a financially driven CVC or a strategically driven one? From a founder’s standpoint, you’ll need to know whether you’re meeting with an investor who views deals through the lens of, “I’m looking for a great team, huge market and a chance to bring in funding and connections to make a business as strong as it can be” or, “I’m looking for a solution/product/platform that I can bring into my company or use to expose my company to a brand new marketplace or technology.”

Once again, the way to determine which type of CVC you’re dealing with is to ask the right questions. In the first meeting, ask about their investment process, how investments are made and whether strategic business unit sponsorship is required for a given deal. The answers will tell you whether the CVC falls into Group 1 or 2, and you’ll be in a strong position to then make choices about whether this potential investor is right for you.

“Look for someone who will understand your business, meet with you and decide that there’s something beyond just capital that will form the basis for that relationship,” says Rick Prostko, managing director at Comcast Ventures. “In today’s venture market, founders want money AND value. Seek out a CVC who has valuable experience to provide, and look for someone who’s been an operator in this segment previously or who has valuable insight and experience to offer.”

What you need to know before you engage with a CVC

Once you’ve done your initial diligence, developed a relationship and determined that a CVC could be a strong investor in your business, there are important factors to be aware of as you move into the next stage of discussions. These include:

Expect deeper product and technical diligence. CVCs can call on technical, product and market experts within their corporation during the due diligence process. As such, their level of product diligence is typically more rigorous than traditional VCs. Be prepared for some grilling by subject matter experts. On the flip side, this diligence process provides you with exposure to potential customers and partners inside the corporation, so use this time to your advantage.

Be aware that you’re going to share confidential information with a large company. “CVCs know that you’re only as good as your reputation,” says Eric Budin, director at Touchdown Ventures . “As such, there are very few examples of CVCs abusing confidential information, because news of it would get around so quickly.”

Still, for a founder, the goal is to be thoughtful and strategic with what you share, and to determine whether the CVC is truly interested in doing a deal before you hand over financial, technical and competitive information. It’s possible that commercial teams at the CVC sponsor could gain unfair advantage from seeing your information, or use their CVC to gain valuable intel on the competition.

On the other hand, sharing your intel could be a fantastic way to get in front of an internal team at the parent company. The key is to think carefully about what you are being asked to share and with whom, and set ground rules with the CVC before they begin diligence.

“It’s important to understand how the corporate fund is structured and how they handle any information that’s shared,” says Prostko. “It might be in your interest to loop in a business unit [within the parent company] that could benefit from learning about your business. On the flip side, if the CVC is a potential competitor, you’ll want to be more careful about what you reveal.”

There will be a risk of regime change. Large companies operate like, well, large companies. People leave, management changes happen and priorities shift. At the outset, ask questions such as: Who will support your company if the commercial manager leading your investment leaves? What will happen to the CVC if the person leading the venture arm is fired? Will they do their pro-rata if the person leading your deal is gone? What happens to any commercial relationships that you might be working on? It’s important to have a keen understanding of internal dynamics before you enter the relationship.

“In general, the more successful a firm is, the more likely the CVC will stick around,” says Allen. “Be sure to look at the individual’s history at the firm, how long he or she has been there, and whether he or she has jumped from fund to fund. If the investing partner has come out of the corporate ‘mother ship,’ and lacks any credible venture experience, buyer beware.”

The CVC may be subject to regulatory rules. Depending on the industry, government regulations may impact how your deal is structured. Banks, for example, are subject to rules that can restrict the percentage of voting stock they can own. Foreign investors may need to comply with CFIUS regulations if your company provides certain specified technologies. Generally, the CVCs will understand the regulations that apply to them. They may not, however, bring them up until late in the process, which could lead to delays.

Commercial transactions with the corporate arm can slow things down. Purely strategic CVCs (Group 2) often require a commercial transaction to happen in connection with a venture deal. The process involved in these transactions often takes longer than the financing process, which can cause issues if the CVC is a key (but not sole) investor in the round. If you’re dealing with a Group 2 CVC, discuss this issue ahead of time to see if you can decouple the two transactions and close the investment prior to inking the commercial deal.

The best way to think about CVC investment

CVCs offer a wealth of capital, human resources and corporate partnerships for startups. But whether you choose to take CVC capital or not, you can benefit from merely approaching CVCs if you have business units operating in either the same space or a tangential space. An initial meeting both gives you an opportunity to do a sales pitch and offers the CVC a chance to vet a product or team and gain some deal insight. For founders, you gain a powerful sales opportunity that might have otherwise taken months or years to obtain.

“Even if you’re told ‘no’ by a CVC, the meeting could result in a good business relationship that could turn into a sales opportunity for you in the near future,” says Prostko.

The WRONG way to think about approaching CVC investors is something along the lines of, “I can’t raise what I want from financial VCs so I’ll go to CVCs as my second choice, since they’re more likely to say ‘yes’ and/or give me better terms.” This attitude will shut doors and cut you off from valuable partners, capital and opportunities to strategically grow your business.

Above all, stay informed as you choose whom to bring in as a partner. Ultimately, it’s your business and the responsibility to ensure that you bring in the right capital partners lies with you.