Have you ever wanted to see one of your “hate-reads” stretched out to feature-film length? If so, you’ll want to watch HBO’s new documentary, “Swiped,” which takes a depressing, trigger-inducing and damning look at online dating culture, and specifically Tinder’s outsized influence in the dating app business.

The film evolved from journalist Nancy Jo Sales’ 2015 Vanity Fair piece, entitled “Tinder and the Dawn of the ‘Dating Apocalypse,” which was criticized at the time for its narrow focus on 20-something, largely heterosexual women in an urban setting. The piece had extrapolated out their personal dating struggles and turned them into condemnation of the entire online dating market.

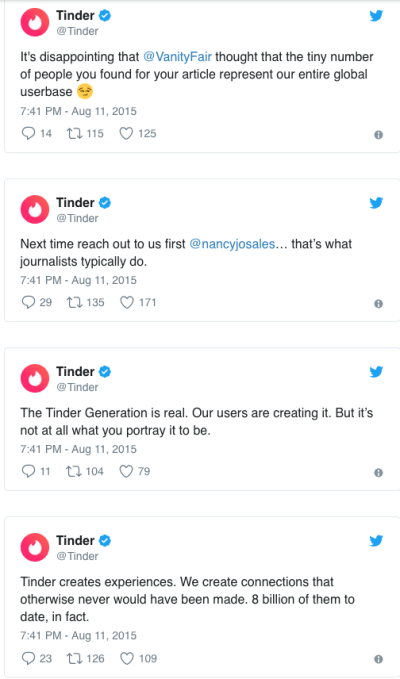

But the VF piece was actually more memorable for Tinder’s response.

The company – well, it went off.

In a 30-tweet tirade (that’s still some of the best of the internet, mind you), the company lost its ever-lovin’ mind on both Vanity Fair and Nancy Jo Sales alike.

In a 30-tweet tirade (that’s still some of the best of the internet, mind you), the company lost its ever-lovin’ mind on both Vanity Fair and Nancy Jo Sales alike.

One sample tweet from the Tinder meltdown: “@VanityFair: Little know fact: sex was invented in 2012 when Tinder was launched.”

Ah, take that! Right?! Right?

Despite the complete PR buffoonery, Tinder had a point.

The VF piece wasn’t representative of Tinder’s larger user base, only a sliver. And the complaints from a few users couldn’t be used to make a point about the entire industry.

Besides, what exactly was unique about those complaints?

Was it truly swipe culture to blame for the mistakes made in dating and sexual experimentation, when you’re young? Don’t you at least once or twice have to choose the wrong person, so you can begin to triangulate on what’s right?

Unfortunately, the film doesn’t fully correct the article’s problem in terms of its demographic samplings.

It still mostly relies on anecdotes told by (usually drunk) 20-somethings, which are then spliced up by the occasional expert commentary.

And the subjects are often really, really drunk.

There’s one scene where a young woman is so wasted, it’s hard to believe she gave the filmmaker informed consent to use her footage.

(Not the one below. But I’m pretty sure those Solo cups aren’t filled with lemonade.)

Meanwhile, the expert commentary has its highlights, too.

There’s one expert – April Alliston, a Princeton professor – who breastfeeds her baby on camera while giving her commentary on pornography. (Oh yes, please discuss rape porn while the baby suckles your breast, thank you very much.)

Look how cool and progressive we are! is the unspoken subtext, even as the film continues to subtly vilify casual sex among young adults, or act as if Tinder itself is somehow entirely responsible for the callous behavior of its users.

Unlike the magazine article, the film does slightly expand its cast of characters to include gender non-conforming and other LGBTQ people, more people of color, and – well, it’s Tinder! – a couple interested in threesomes.

But the general slice of the Tinder user base interviewed remains young, urban, and, in some cases, fairly vapid.

As for “Swiped’s” milieu, much of its action is in the city.

Specifically, scene after scene in the film is labeled, “New York, New York,” as if the experiences of people in this competitive and unique market – a place where leveling up to something better is a way of life – could somehow represent a universal truth applicable to all of Tinder’s estimated 50 million users.

The film does, however, cover nearly everything that’s awful about dating apps – from young men ordering girls to their door as if it’s a meal from Seamless, to the overwhelming sense of dread and the depression that results from being on dating apps – or really, the internet itself – for too long.

There are also scenes touching nearly every Tinder trope:

The sending of dick pics; men posing with fish in their profile photos; that supposedly happy couple “looking for a third” (spoiler alert: they’re not happy and are broken up by end of film); the “DTF?” come-ons; and basically every other reason people delete these apps in the first place.

The sending of dick pics; men posing with fish in their profile photos; that supposedly happy couple “looking for a third” (spoiler alert: they’re not happy and are broken up by end of film); the “DTF?” come-ons; and basically every other reason people delete these apps in the first place.

Where the film is somewhat stronger is when it talks about the very real psychological tricks Tinder and other dating apps have adopted to keep users engaged and addicted to swiping.

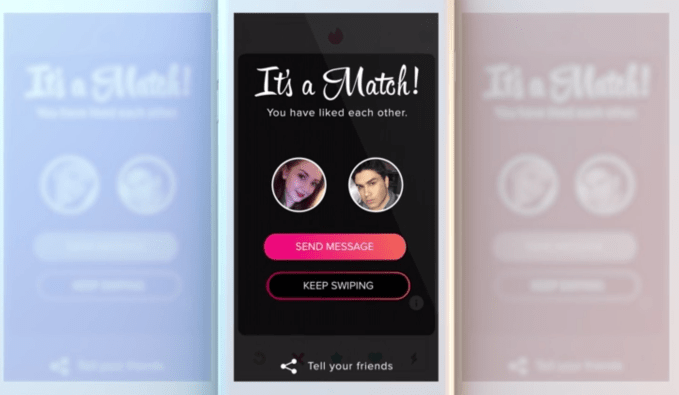

Tinder, it’s pointed out, uses gamification techniques: Brain tricks like intermittent variable rewards that are proven to work on pigeons, no less!

You see, if you don’t know when you’re getting the reward – a treat, a match, etc. – you end up playing the game more often, the psychologists explain.

One of the better quotes on this topic comes from Tinder co-founder and CSO Jonathan Badeen, where he essentially compares the act of using Tinder to doing drugs or gambling.

“We have some of these game-like elements, where you almost feel like you’re being rewarded,” says Baden. “It kinda works like a slot machine, where you’re excited to see who the next person is, or, hopefully, you’re excited to see ‘did I get the match?’ and get that ‘It’s a Match’ screen? It’s a nice little rush,” he enthuses.

Yeah.

Yikes.

Of course, these are concerns that extend beyond the online dating app industry.

Social media apps, in general, have been more recently called out for similar behaviors – that is, for leveraging psychological loopholes to addict their users in unhealthy ways.

The ramifications of our smartphone addictions are only now being examined, in fact.

Apple and Google, for example, have just launched screen time controls aimed at giving us a chance at fighting back at the dangerous dark patterns and brain hacks these apps use. (Apple’s toolset is only arriving in iOS 12 – which is just now getting to the public.)

It’s certainly fair to criticize companies like Tinder and Bumble for bringing these gamification tricks into delicate areas like those where the focus is supposedly on forming real human connections or “finding love.” But it’s disingenuous to act as if this is something unique to Tinder (et al) and not just, generally, the god-awful state of the tech industry as a whole at present.

The only other worthwhile part to “Swiped” is where the film points out that no one knows if any of these addictive apps actually succeed in helping people find real relationships.

Dating app companies don’t have any data on how many lasting relationships result from their app’s usage, “Swiped” finds. It’s odd, as tech companies are usually data hungry beasts. And success rates would seemingly be the exact kind of metric a company claiming to solve issues around relationship-finding would want to track.

Though everyone today seems to know someone who “met on an app,” it’s unclear what portion of the user base is actually finding long-term success with those relationships. The dating app companies have no idea, either, the film proclaims.

Asked how many people who met on Tinder got married or ended up in committed relationships, Jessica Carbino, a sociologist at Tinder, tells the filmmaker: “we do not have that information available.” She then adds she’s “inundated with emails” from Tinder users getting married and having babies.

(She also hilariously defends casual hookups as something that people go to church to pursue, too, so don’t blame Tinder for that! I mean, sometimes this film is just comedy gold, I swear.)

Of course, with a user base in the tens of millions, a good handful of happy emails should be expected. It’s definitely not evidence that Tinder is any better than the alternative – bars, blind dates, introductions through friends, etc.

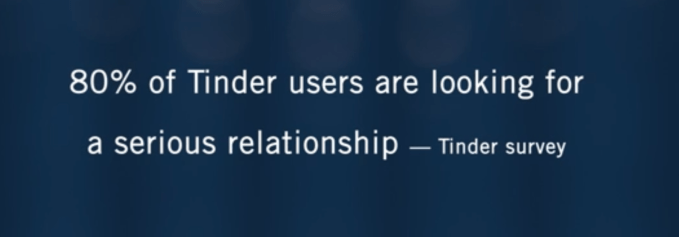

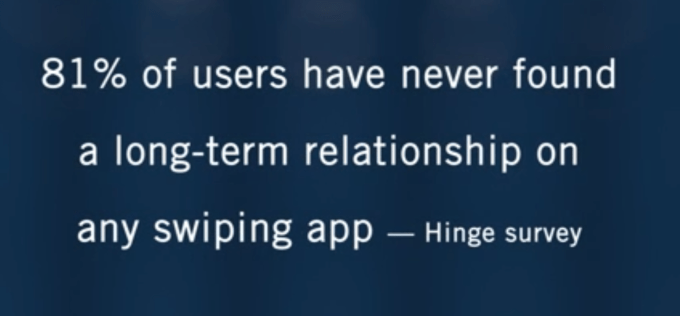

The film then drives this particular point home by citing user studies by both Tinder and the more relationship-focused dating app Hinge, which seem indicate that swiped-based dating doesn’t work.

“80% of Tinder users are looking for a serious relationship,” says one Tinder survey. The text then fades, and the next statistic, this time from Hinge, appears.

“81% of users have never found a long-term relationship on any swiping app,” it says.

By the end of the film, it’s clear you’re expected to delete Tinder and all the other dating apps off your phone and get on with your life.

However, as with Facebook and social media, backlash doesn’t mean abandonment.

Tinder’s swipe culture is the new normal. It’s right to hold it accountable in areas it can do better – reporting and abuse, for example – but it’s not going away anytime soon.