The McLaren Senna GTR shouldn’t exist.

This feat of engineering and design isn’t allowed on public roads. It’s built for the track, but prohibited from competing in motorsports. And yet, the GTR is no outlier at McLaren. It’s part of their Ultimate Series, a portfolio of extreme and distinct hypercars that now serve as the foundation of the company’s identity and an integral part of their business model.

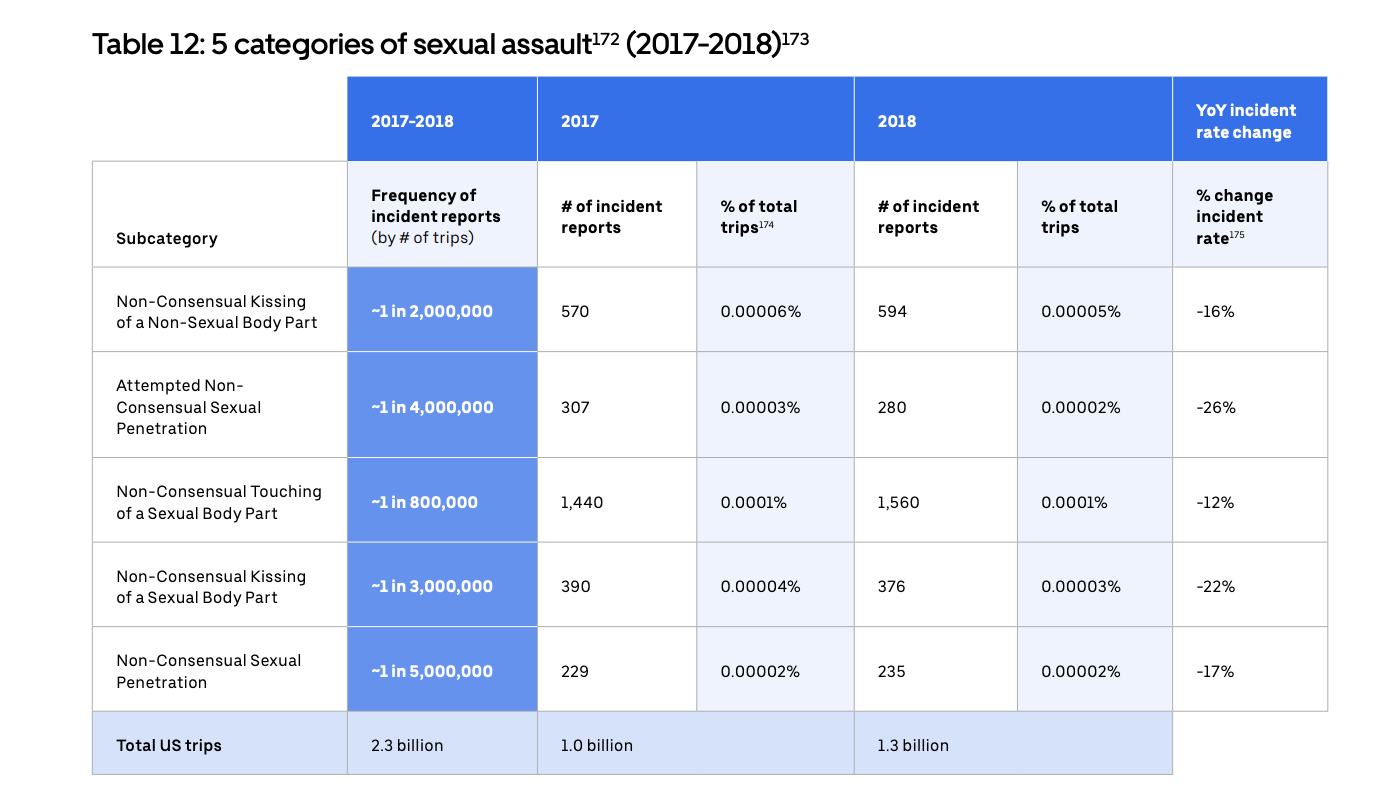

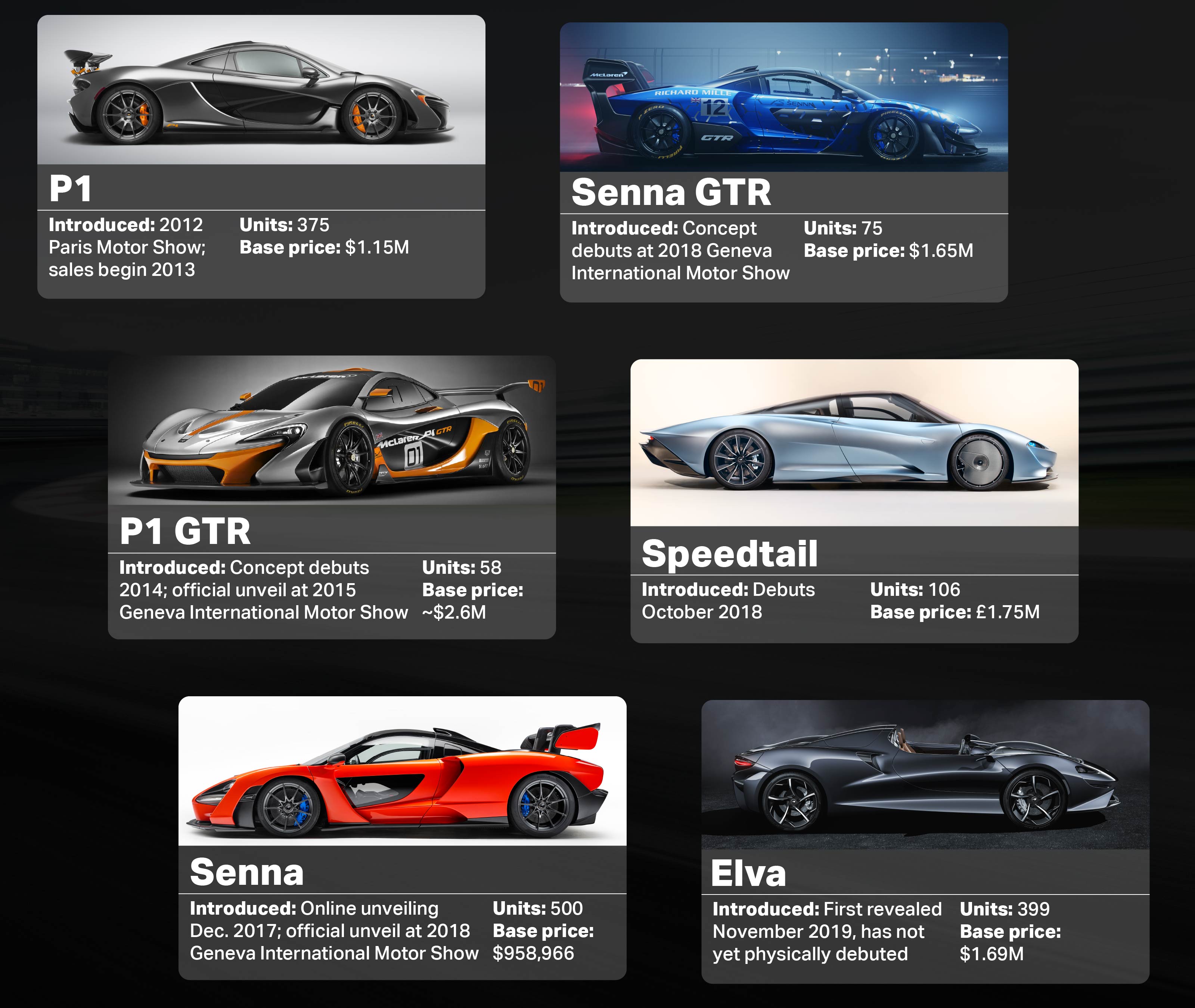

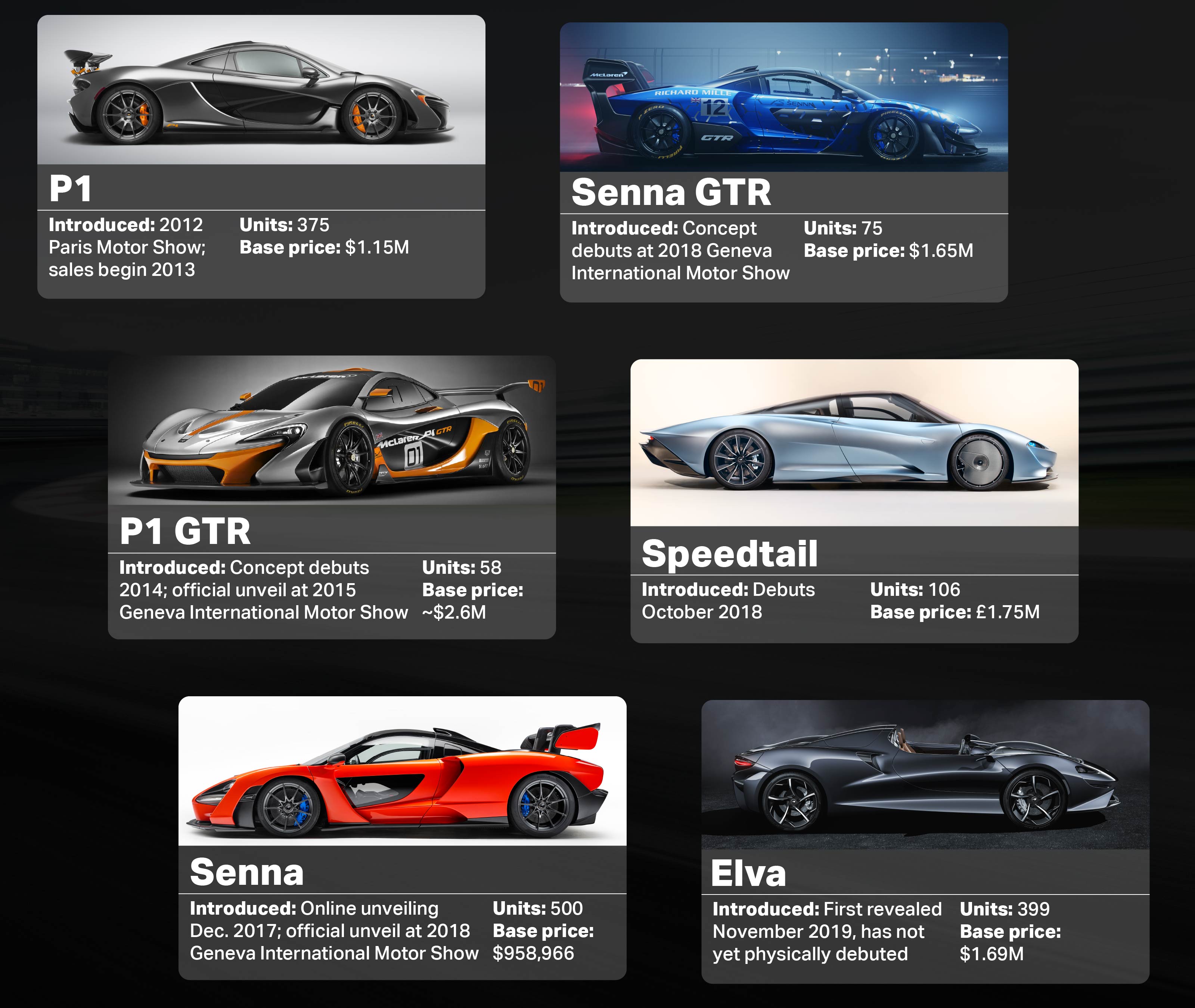

The P1, introduced in 2012, was McLaren Automotive’s opening act on the hypercar stage and was an instant success for both the brand and its business. McLaren followed it up with the P1 GTR, then went on to chart a course toward the Ultimate Series of today and beyond.

Since 2017, the automaker has added the Senna, Speedtail, Senna GTR and now the open-cockpit Elva to the Ultimate Series portfolio. While the GTR is certainly the most extreme and limited in how and where it can be used, it follows a larger pattern of the Ultimate Series as being provocatively designed with obsessive intent.

Automotive takes the wheel

Purpose-built race cars that call on every modern tool of engineering and design have historically been produced for one purpose: winning. This objective, nourished by billions of dollars of investment from the motorsports industry, has led to technological and performance breakthroughs that have eventually trickled down to automotive.

The pipeline that has produced a century of motorsports-driven innovation is narrowing as racing regulations become more restrictive. Now, a new dynamic is taking shape. Automotive is taking the technological lead.

Take the McLaren Senna road car, the predecessor to the GTR. McLaren had to constrain the design of the Senna to make it road legal. But the automaker loaded it with active aerodynamics and chassis control systems that racing engineers could only dream about.

McLaren wasn’t finished. It pushed the bounds further and produced a strictly track-focused and unconstrained race car that expands upon the Senna’s lack of conformity. The Senna GTR might be too advanced and too fast for any racing championship, but McLaren said to hell with it and made the vehicle anyway.

The bet paid off. All 75 Senna GTR hypercars, which start at $1.65 million, sold before the first one was even produced.

The Senna GTR is the symbol of a new reality — a hypercar market that thrives on the ever-more-extreme, homologation standards be damned.

Two weeks ago, I had a chance to get behind the wheel of the Senna GTR at the Snetterton Circuit in the U.K. to find out how McLaren went about developing this wholly unconstrained machine.

Behind the wheel

Rr-rr-rr-kra-PAH! The deafening backfire of the GTR’s 814-horsepower 4.0-liter twin-turbo V8 engine snapped me to attention and instantly transported me to the moment earlier in the day that provided the first hints of what my drive might be like.

Rob Bell, the McLaren factory driver who did track development for the GTR, was on hand to get the car warmed up. Shortly after he set out, the car ripped down the front-straight, climbing through RPMs with an ear-protection-worthy scream that reverberated off every nearby surface, an audible reminder of how unshackled it is.

As Bell approached Turn 1, the rear wing quickly dropped back to its standard setting from the straightaway DRS (drag reduction system) position, then to an even more aggressive airbrake as he went hard to the brakes from 6th gear down to 5th to 4th. The vehicle responded with the signature kra-PAH! kra-PAH! and then promptly discharged huge flames out the exhaust as the anti-lag settings keep a bit of fuel flowing off-throttle.

I thought to myself, ‘Holy sh*t! This thing is no joke!’

Sliding into the driver’s seat, I feel at home. The cockpit is purposeful. The track was cold with some damp spots, and the GTR is a stiff, lightweight race car with immense power on giant slick tires. Conventional wisdom would suggest the driver — me in this case — should slowly work up to speed in these otherwise treacherous conditions. However, the best way to get the car to work is to get temperature in the tires by leaning on it a bit right away. Bell sent me out in full “Race” settings for both the engine and electronic traction and stability controls. Within a few corners — and before the end of the lap — I had a good feel for the tuning of the ABS, TC and ESC, which were all intuitive and minimally invasive.

As a racing driver, it’s rare to feel a tinge of excitement just to go for a drive. As professionals, driving is a clinical exercise. But the GTR triggered that feeling.

I started by pushing hard in slower corners and before long worked my way up the ladder to the fast, high-commitment sections. The car violently accelerated up through the gears, leaving streaks of rubber at the exit of every corner.

Once the car is straight, drivers can push the DRS button to reduce drag and increase speed for an extra haptic kick. The DRS button is now a manual function on the upper left of the steering wheel to give the driver more control over when it’s deployed. After hitting the DRS, the car dares you to keep your right foot planted on the throttle, then instantly hunkers down under braking with a stability I’ve rarely experienced.

The active rear wing adds angle while the active front flaps take it out to counterbalance the effect of the car’s weight shifting forward onto the front axle, letting you drive deeper and deeper into each corner. It’s sharply reactive; the GTR stuck to the road, but still required a bit of driving with my fingertips out at the limit on that cold day. I soon discovered that the faster I went, the more downforce the car generated, and the more speed I was able to extract from it.

Tip to tail

In almost any other environment, the Senna road car is the most shocking car you’ve ever seen. Its cockpit shape is reminiscent of a sci-fi spaceship capsule. The enormous swan neck-mounted rear wing is one highlight in a long list of standout features. The Senna road car looks downright pedestrian next to the GTR.

The rear wing stretches off the back of the car with sculpted carbon fiber endplates and seamlessly connects to the rear fender bodywork. The diffuser that emerges from the car’s underbody — creating low pressure by accelerating the airflow under the car for added downforce — is massive. The giant 325/705-19 Pirelli slicks are slightly exposed from behind, giving you the full sense of just how much rubber is on the ground, and the sharp edges of the center exit exhaust tips are already a bluish-purple tint.

The cockpit shape and dihedral doors are instantly recognizable from the road car. But inside, the GTR is all business. The steering wheel is derived from McLaren’s 720S GT3 racing wheel, a butterfly shape with buttons and rotary switches aplenty. The dash is an electronic display straight out of a race car; six-point belts and proper racing seats complete the aesthetic.

Arriving at the front of the car, the active front wing-flaps are as prominent as ever, while the splitter extends several inches farther out in front of the car and is profiled with a raised area in the center to reduce pitch sensitivity given the car’s much lower dynamic ride-height. In fact, nearly the entire front end of the car has been tweaked; there are additional dive-planes, the forward facing bodywork at the sides of the car have been squared-off and reshaped, and an array of vortex generators have been carved into the outer edge of the wider, bigger splitter surface.

All of these design choices in the front point to the primary area of development from the Senna road-car to the GTR: maximizing its l/d or ratio of lift (in this case the inverse of lift, downforce) to drag.

McLaren pulled two of its F1 aerodynamicists into the GTR project to take the car’s aero to a new level. The upshot: a 20% increase in the car’s total downforce compared to the Senna road car, while increasing aero efficiency — the ratio of downforce to drag — by an incredible 50%. The car is wider, lower and longer than its road-going counterpart, and somehow looks more properly proportioned with its road-legal restrictions stripped away to take full advantage of its design freedom.

This was the car the Senna always wanted to be.

The development process of the GTR was short and to the point. When you have F1 aerodynamicists and a GT3 motorsport program in-house attacking what is already the most high-performing production track car in the industry, it can be. There were areas they could instantly improve by freeing themselves of road-car constraints — the interior of the car could be more spartan; the overall vehicle dimensions and track width could increase; the car would no longer need electronically variable ride heights for different road surfaces so the suspension system could be more purposeful for track use; the car would have larger, slick tires.

All this provided a cohesive mechanical platform upon which to release the aerodynamic assault of guided simulation and CFD.

The GTR benefits from the work of talented humans and amazing computer programs working together with a holistic design approach. What was once a sort of invisible magic, aerodynamics has become a well-understood means of generating performance. But you still have to know what you’re seeking to accomplish; the priorities for a car racing at Pikes Peak are much different than those of a streamliner at Bonneville.

The development team for the GTR sought to maximize the total level of downforce that the tires could sustain, then really kicked their efforts into gear to clean up airflow around the car as much as possible. Many of the aggressive-looking design elements that differentiate the GTR from the Senna are not just for additional downforce but to move air around the car with less turbulence — less turbulent air means less drag. You can’t see it or feel it, but it certainly shows up on the stopwatch, and is often the difference between a car that just looks fast and one that actually is.

I hadn’t asked how fast the car was relative to other GT race cars before I drove it. I think a part of me was fearful that despite its appearance and specs it might be wholly tuned down to be sure it was approachable for an amateur on a track day. And that would make sense, as that’s the likely use-case this car will have. After driving the GTR, I didn’t hesitate for a second to ask, to which they humbly said that it’s seconds faster than their own McLaren 720S GT3 car, and still had some headroom.The Senna GTR is another exercise in exploring the limits of technology, engineering and performance for McLaren, enabled by a market of enthusiasts with the means to support it. And this trend is likely to continue unless motorsports changes the rules to allow hypercars.

McLaren’s next move

The Automobile Club de l’Ouest, organizers of the FIA World Endurance Championship, which includes the 24 Hours of Le Mans, has been working for years to develop regulations that could include them. While these discussions are gaining momentum, it remains to be seen whether motorsport can provide a legitimate platform for the hypercar in the modern era.

The last time this kind of exercise was embarked on was more than 20 years ago during the incredible but short-lived GT1-era at Le Mans that spanned from 1995 to 1998. It saw McLaren, Porsche, Mercedes and others pull out all the stops to create the original hypercars — in most cases comically unroadworthy homologation specials like the Porsche 911 GT1 Strassenversion (literally “street version”) and Mercedes CLK GTR — for the sole purpose of becoming the underpinnings of a winning race car on the world’s stage.

At that time, the race cars made sense to people; the streetcars were misfits of which only the necessary minimum of 25 units were produced in most cases, and the whole thing collapsed due to loopholes, cost, politics and the lack of any real endgame.

Today, the ACO benefits from a road-going hypercar market that McLaren played a key role in developing. Considering McLaren’s success with hyper-specific specialized vehicles in recent years, I’d bet the automaker could produce a vehicle custom-tailored to a worthy set of hypercar regulations. Even if not, McLaren will continue to develop and sell vehicles under its Ultimate Series banner.

And there’s already evidence that McLaren is doubling down.

McLaren shows off the open cockpit Elva.

McLaren’s Track 25 business plan targets $1.6 billion in investment toward 18 new vehicles between 2018 and 2025. The company’s entire portfolio will use performance-focused hybrid powertrains by 2025.

The paint had barely dried on the Senna GTR before McLaren introduced another new vehicle, the Elva. And more are coming. McLaren is already promising a successor to the mighty P1. I, for one, am looking forward to what else they have in store.