There’s money, and then there’s wealth. In all likelihood, money is what most of us have (or don’t have). It’s what we use to buy lunch, pay rent or put a down payment on a house. Wealth, on the other hand, is what buys yachts. But more than superficial material things, wealth also buys financial security (and all the good and ill that comes with it) for subsequent generations.

What is a family office?

Although close to half of Americans hold no stocks, bonds or real estate, most of the remaining half that are lucky and prosperous enough to do so choose to manage their assets on their own, or perhaps with the help of a financial advisor. But as you move further along the privileged end of the socio-economic curve, managing, preserving and growing one’s wealth becomes more complicated.

Many of the world’s highest-net-worth (HNW) families employ an entire office full of accountants, lawyers and investment professionals to manage their assets. These “family offices” sometimes manage the assets of more than one family, but they are still relatively close-knit.

Historically, family offices haven’t made many direct investments into individual tech startups, instead favoring a more diversified approach to tech investing by being limited partners in venture capital and other private-market funds. Or, outside of tech, they invest in public-market equities, real estate, fixed income or other “alternative” asset classes besides VC, PE and hedge funds, according to a 2017 article about ultra HNW investors’ portfolios from KKR.

Increasingly, however, family offices are investing more into individual tech startups, at least according to anecdotal reports and a recent funding round Crunchbase News covered. But one anecdote doesn’t document a trend, so let’s take a look at the numbers.

Family offices’ direct investment into startups picked up the pace

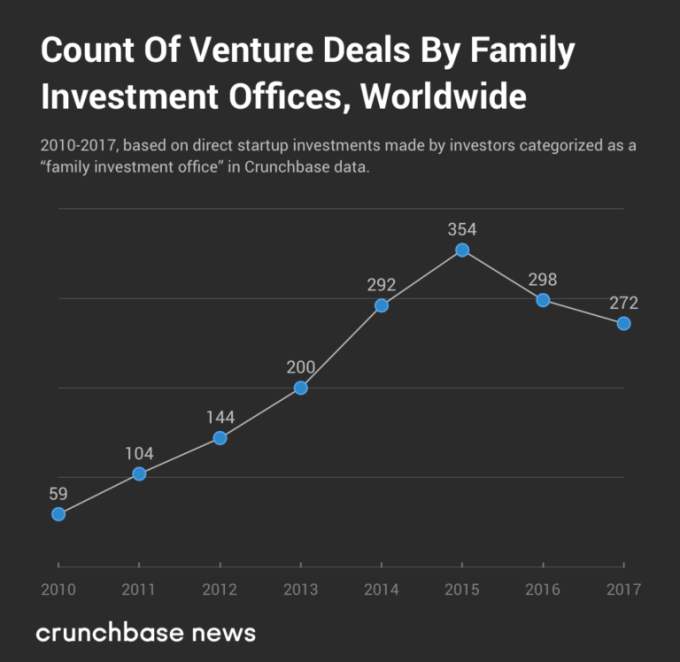

Data covering direct startup investments from family offices listed in Crunchbase bears out that trend. The chart below is based on more than 1,700 venture deals (seed, angel, equity crowdfunding, Series A, Series B, etc.) struck with individual technology companies by 193 family offices located around the world.

The 193 family offices with listed venture investments are, no doubt, only a fraction of the total count of such groups, which tend to be private. Combined with the fact that many startups are slow to announce funding, it’s not like the list of funding rounds or their participants is comprehensive. However, assuming it’s fairly representative, we can treat the figure above as a directional indicator of general trends.

And what are those trends?

First off, at least when it comes to deal volume, family offices’ startup investment activity tracks with the broader venture investment market (which includes individual angels, venture capital groups, seed funds, accelerators and others).

During the several years leading up to 2015, there was a run-up in the number of deals being struck. After that high point, though, deal volume began to decline in the U.S., which Crunchbase News has documented, as investors eschewed writing many smaller checks to early-stage startups, instead favoring fewer, larger checks with later-stage tech companies. On a global scale, projected deal volume is roughly flat on an annualized basis from 2015 through 2017, whereas reported deal data is down primarily due to reporting delays. Because there are more U.S. family offices that invest in startups than international ones, it’s not surprising to see that family office deal volume hews closer to the U.S. market in general.

Family office venture deal volume growth outpaced VC

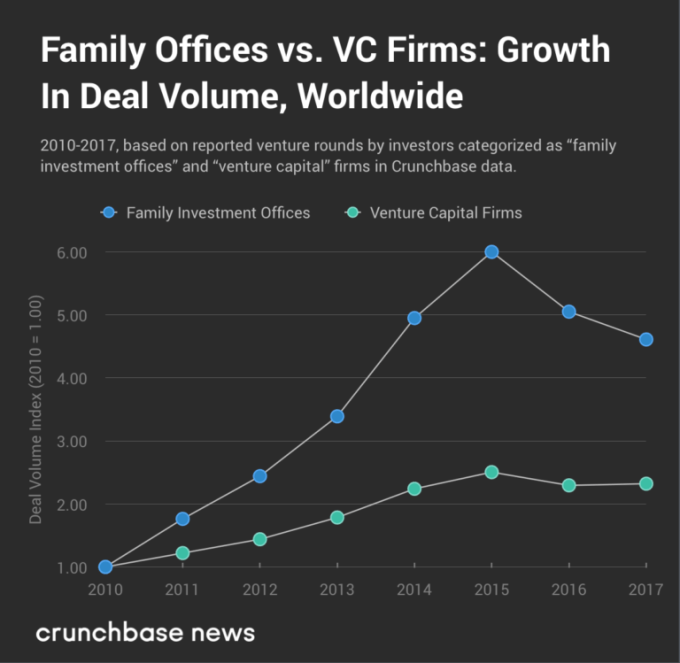

But what’s different about family offices — and what lends credence to the anecdotal evidence suggesting there are more family offices investing in more startups — is the growth rate in deal volume over time as compared to institutional venture capital investors. To be sure, worldwide, there were more deals struck by both types of investor in 2017 than in 2010 (even when accounting for reporting delays). But the difference between these two types of investor is in the magnitude of the change.

In the chart below, we compare reported deal volume between VC funds (which have a lot of known deals per year) and family offices (which, as we showed above, have much fewer recorded startup investment deals per year). We adjust for this discrepancy in deal volume by indexing reported deal volume against 2010 levels. In doing so, we’re able to deliver a relativistic, apples-to-apples comparison between the two.

Worldwide, in 2015, reported deal volume from VC firms was almost precisely 2.5x that of 2010’s totals. But that multiple for family offices is roughly 6x. And, although it isn’t pictured above, family office deal volume growth outperformed traditional VC between 2011-2017, 2012-2017 and 2013-2017.

In relative terms, across a range of measures, deal volume growth was higher and faster among family offices than VC funds for a significant period of time. The data suggest that family offices making direct investments into startups recently became a trend. Especially for that period through 2014, family offices were on the early side of the adoption curve for making direct startup investments. Whatever growth we see on the VC side is the product of growth in the market in general, but it’s not like VC funds are still adopting direct startup investments into their repertoire. It’s been their model for decades. For comparatively stodgy family offices, it was still the new, new thing.

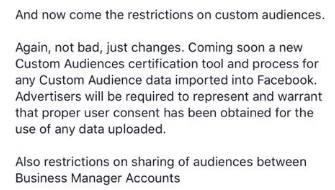

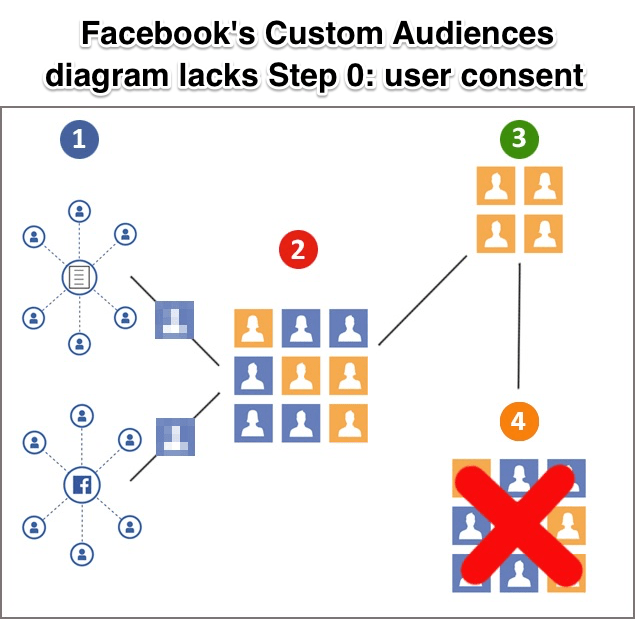

This snippet of a message sent by a Facebook rep to a client notes that “for any Custom Audiences data imported into Facebook, Advertisers will be required to represent and warrant that proper user content has been obtained.”

This snippet of a message sent by a Facebook rep to a client notes that “for any Custom Audiences data imported into Facebook, Advertisers will be required to represent and warrant that proper user content has been obtained.”

Last week Facebook

Last week Facebook