It’s easier than ever to build software, which makes it harder than ever to build a defensible software business. So it’s no wonder investors and entrepreneurs are optimistic about the potential of data to form a new competitive advantage. Some have even hailed data as “the new oil.” We invest exclusively in startups leveraging data and AI to solve business problems, so we certainly see the appeal — but the oil analogy is flawed.

In all the enthusiasm for big data, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that all data is not created equal. Startups and large corporations alike boast about the volume of data they’ve amassed, ranging from terabytes of data to quantities surpassing all of the information contained in the Library of Congress. Quantity alone does not make a “data moat.”

Firstly, raw data is not nearly as valuable as data employed to solve a problem. We see this in the public markets: companies that serve as aggregators and merchants of data, such as Nielsen and Acxiom, sustain much lower valuation multiples than companies that build products powered by data in combination with algorithms and ML, such as Netflix or Facebook. The current generation of AI startups recognize this difference and apply machine learning models to extract value from the data they collect.

Even when data is put to work powering ML-based solutions, the size of the data set is only one part of the story. The value of a data set, the strength of a data moat, comes from context. Some applications require models to be trained to a high degree of accuracy before they can provide any value to a customer, while others need little or no data at all. Some data sets are truly proprietary, others are readily duplicated. Some data decays in value over time, while other data sets are evergreen. The application determines the value of the data.

Defining the “data appetite”

Machine learning applications can require widely different amounts of data to provide valuable features to the end user.

MAP threshold

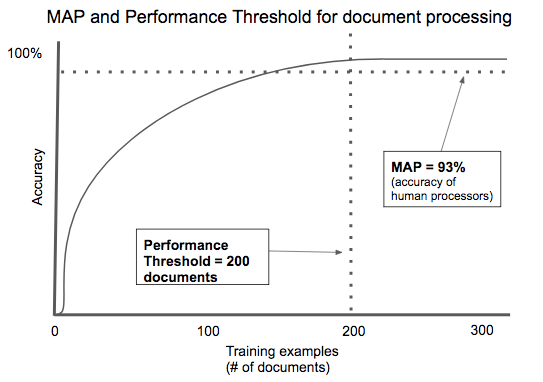

In the cloud era, the idea of the minimum viable product (or MVP) has taken hold — that collection of software features which has just enough value to seek initial customers. In the intelligence era, we see the analog emerging for data and models: the minimum level of accurate intelligence required to justify adoption. We call this the minimum algorithmic performance (MAP).

Most applications don’t require 100 percent accuracy to create value. For example, a productivity tool for doctors might initially streamline data entry into electronic health record systems, but over time could automate data entry by learning from what doctors enter in the system. In this case, the MAP is zero, because the application has value from day one based on software features alone. Intelligence can be added later. However, solutions where AI is central to the product (for example, a tool to identify strokes from CT scans), would likely need to equal the accuracy of status quo (human-based) solutions. In this case the MAP is to match the performance of human radiologists, and an immense volume of data might be needed before a commercial launch is viable.

Performance threshold

Not every problem can be solved with near 100 percent accuracy. Some problems are too complex to fully model given the current state of the art; in that case, volume of data won’t be a silver bullet. Adding data might incrementally improve the model’s performance, but quickly hit diminishing marginal returns.

At the other extreme, some problems can be solved with near 100 percent accuracy with a very small training set, because the problem being modeled is relatively simple, with few dimensions to track and few variations in outcome.

In short, the amount of data you need to effectively solve a problem varies widely. We call the amount of training data needed to reach viable levels of accuracy the performance threshold.

AI-powered contract processing is a good example of an application with a low performance threshold. There are thousands of contract types, but most of them share key fields: the parties involved, the items of value being exchanged, time frame, etc. Specific document types like mortgage applications or rental agreements are highly standardized in order to comply with regulation. Across multiple startups, we’ve seen algorithms that automatically process documents needing only a few hundred examples to train to an acceptable degree of accuracy.

AI-powered contract processing is a good example of an application with a low performance threshold. There are thousands of contract types, but most of them share key fields: the parties involved, the items of value being exchanged, time frame, etc. Specific document types like mortgage applications or rental agreements are highly standardized in order to comply with regulation. Across multiple startups, we’ve seen algorithms that automatically process documents needing only a few hundred examples to train to an acceptable degree of accuracy.

Entrepreneurs need to thread a needle. If the performance threshold is high, you’ll have a bootstrap problem acquiring enough data to create a product to drive customer usage and more data collection. Too low, and you haven’t built much of a data moat!

Stability threshold

Machine learning models train on examples taken from the real-world environment they represent. If conditions change over time, gradually or suddenly, and the model doesn’t change with it, the model will decay. In other words, the model’s predictions will no longer be reliable.

For example, Constructor.io is a startup that uses machine learning to rank search results for e-commerce websites. The system observes customer clicks on search results and uses that data to predict the best order for future search results. But e-commerce product catalogs are constantly changing. A model that weighs all clicks equally, or trained only on a data set from one period of time, risks overvaluing older products at the expense of newly introduced and currently popular products.

Keeping the model stable requires ingesting fresh training data at the same rate that the environment changes. We call this rate of data acquisition the stability threshold.

Perishable data doesn’t make for a very good data moat. On the other hand, ongoing access to abundant fresh data can be a formidable barrier to entry when the stability threshold is low.

Identifying opportunities with long-term defensibility

The MAP, performance threshold and stability threshold are all central elements to identifying strong data moats.

First-movers may have a low MAP to enter a new category, but once they have created a category and lead it, the minimum bar for future entrants is to equal or exceed the first mover.

Domains requiring less data to reach the performance threshold and less data to maintain that performance (the stability threshold) are not very defensible. New entrants can readily amass enough data and match or leapfrog your solution. On the other hand, companies attacking problems with low performance threshold (don’t require too much data) and a low stability threshold (data decays rapidly) could still build a moat by acquiring new data faster than the competition.

More elements of a strong data moat

AI investors talk enthusiastically about “public data” versus “proprietary data” to classify data sets, but the strength of a data moat has more dimensions, including:

- Accessibility

- Time — how quickly can the data be amassed and used in the model? Can the data be accessed instantly, or does it take a significant amount of time to obtain and process?

- Cost — how much money is needed to acquire this data? Does the user of the data need to pay for licensing rights or pay humans to label the data?

- Uniqueness — is similar data widely available to others who could then build a model and achieve the same result? Such so-called proprietary data might better be termed “commodity data” — for example: job listings, widely available document types (like NDAs or loan applications), images of human faces.

- Dimensionality — how many different attributes are described in a data set? Are many of them relevant to solving the problem?

- Breadth — how widely do the values of attributes vary? Does the data set account for edge cases and rare exceptions? Can data or learnings be pooled across customers to provide greater breadth of coverage than data from just one customer?

- Perishability — how broadly applicable over time is this data? Is a model trained from this data durable over a long time period, or does it need regular updates?

- Virtuous loop — can outcomes such as performance feedback or predictive accuracy be used as inputs to improve the algorithm? Can performance compound over time?

Software is now a commodity, making data moats more important than ever for companies to build a long-term competitive advantage. With tech titans democratizing access to AI toolkits to attract cloud computing customers, data sets are one of the most important ways to differentiate. A truly defensible data moat doesn’t come from just amassing the largest volume of data. The best data moats are tied to a particular problem domain, in which unique, fresh, data compounds in value as it solves problems for customers.

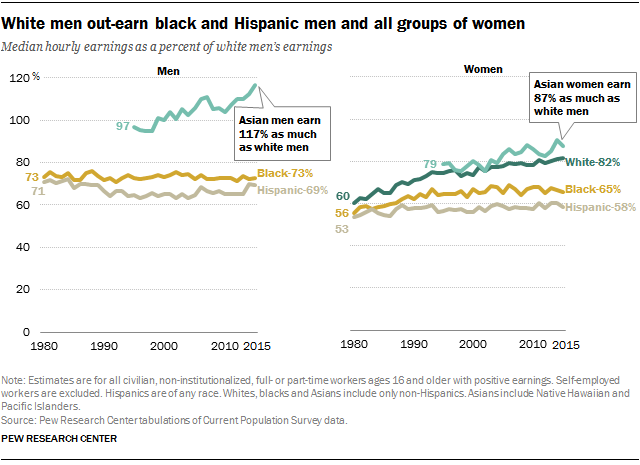

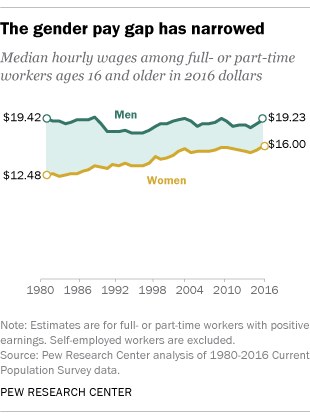

The racial pay gap also continues to exist. Similar to the gender pay gap, the racial pay gap has narrowed in recent years, but white men continue to out-earn black and Hispanic men, and all groups of women.

The racial pay gap also continues to exist. Similar to the gender pay gap, the racial pay gap has narrowed in recent years, but white men continue to out-earn black and Hispanic men, and all groups of women.